Winning the Peace in Humanitarian Emergencies

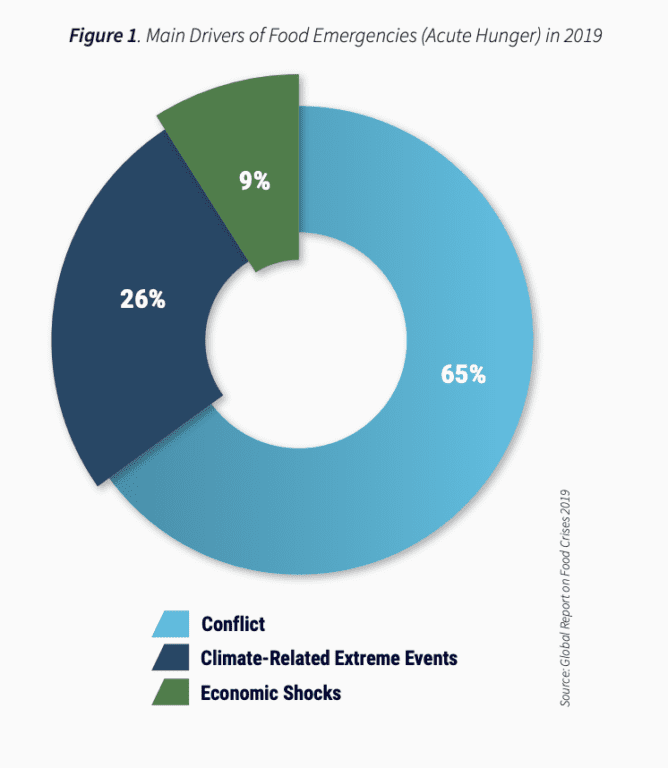

While the COVID-19 pandemic is devastating communities worldwide, it’s conflict that remains the biggest cause of hunger today. Violence and instability displaces people, topples markets and destroys infrastructure. Our latest report Winning the Peace in Humanitarian Emergencies shows that people living in conflict-affected countries are more than 2.5 times more likely to experience hunger than others.

As famously stated by the economist Paul Collier, “War is development in reverse.”

A few more key stats to give you the full picture:

- About two-thirds of the United Nations World Food Programme’s (WFP) assistance goes to countries facing conflict.

- Conflict drives hunger in 80 percent of the world’s biggest food crises, and is the cause of hunger for around 77 million people in at least 22 countries.

- 60 percent of the world’s hungriest people live in countries affected by violence and conflict.

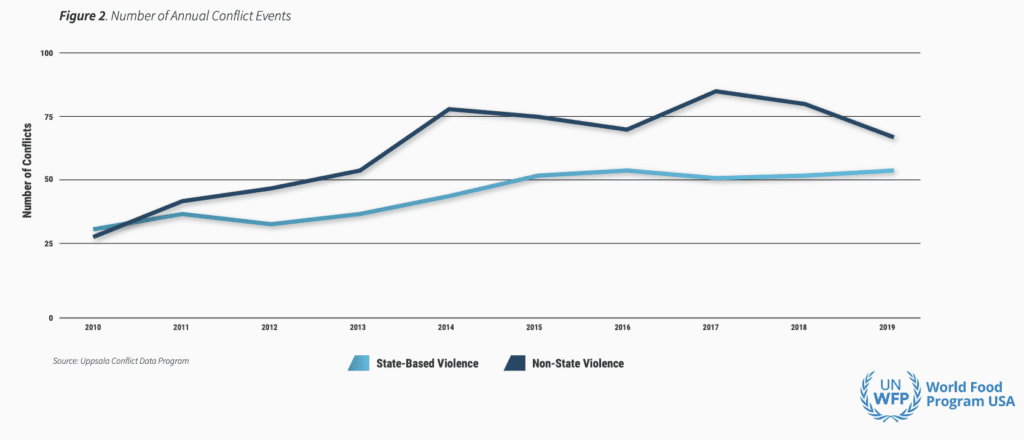

Conflict Is on the Rise

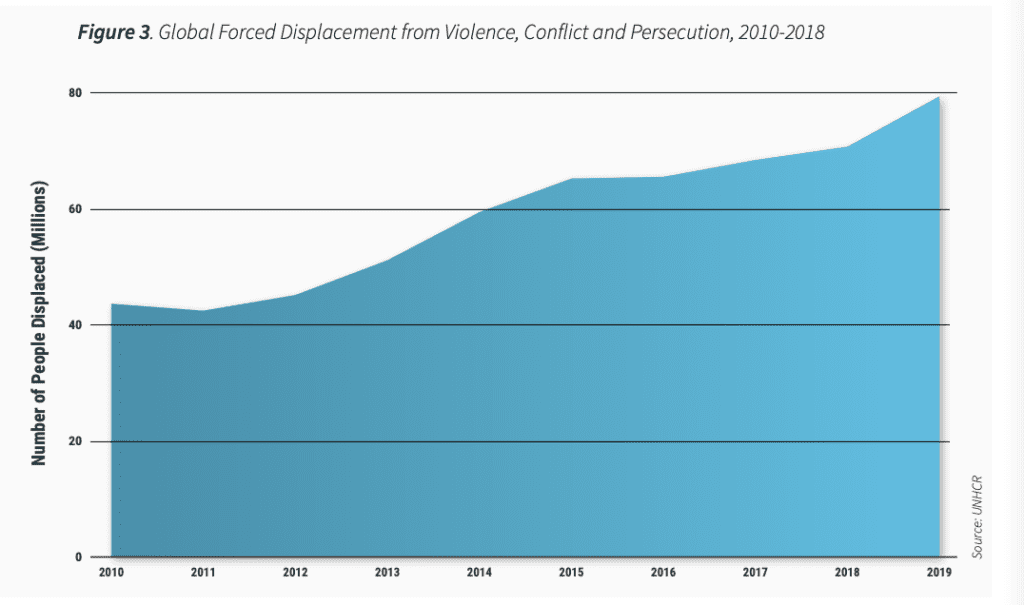

Violent conflicts have tripled in the past decade, forcing more and more people to flee fighting and persecution.

In fact, today, 79.5 million people – a full one percent of humanity – are displaced from their homes, more than any other time in recorded history. Almost 30 million of them have crossed borders seeking refuge, settling in low-income countries already struggling to meet their own needs.

In 2018, the United Nations Security Council recognized, for the first time, that conflict and violence are closely linked to hunger and famine, condemning the use of starvation as a weapon of war.

Hunger and Instability

We know hunger is a result of war. Now, we’re learning that the inverse is also true: hunger drives instability. Here’s how:

- Hunger and instability are mutually reinforcing.

- Food can become a weapon of war. Groups fuel conflict by controlling food production, denying food to enemies, and exploiting hunger and poverty.

- Armed groups can use food insecurity to undermine governments.

- Sometimes the response to food insecurity can do more harm than good. Governments trying to alleviate food insecurity with reduced import tariffs and export restrictions can unintentionally cause instability in other countries.

- Food-related instability is not limited to violent conflict. Food price protests often occur among well-off communities suffering from temporary food insecurity, but not chronic hunger.

- Modern conflicts are almost never driven by a single cause. The strongest indicator of likely violence is a history of violence. It’s a warning against the dramatic oversimplification that “all hungry people are violent, and all violent people are hungry.”

A woman farms in Lake Chad in the Sahel. Climate there has caused the lake to shrink by 90% and given rise to increased Boko Haram violence, creating one of the worst humanitarian crises in the world.

What Causes Food-Related Conflict?

Competition over dwindling natural resources, rising food prices and extreme weather all drive food-related instability today.

In the last half century, nearly half of all civil wars have been linked to competition over natural resources. Rural populations survive on agriculture: When there aren’t enough resources like land and water to sustain their livelihoods, you can bet that conflict will follow.

Meanwhile, social unrest often happens when food is hard to get. There’s no substitute for food, after all, even when prices are high. It’s a vicious feedback loop, where conflict tremendously increases the price of food.

In 2020, for example, the cost of a simple meal in South Sudan exceeds 186 percent of daily income.

And climate change is directly linked to violent conflict. Its growing impact is being felt most severely in the Global South where droughts, floods and extreme weather events have become more frequent and intense. In fact, they’ve more than doubled in frequency over the last 25 years. The Sahel, in particular, is a climate change hotspot – and it’s home to a growing number of extremist organizations, including Boko Haram, al-Qaeda and Al Shabab. There and in other regions, a combination of population growth, pervasive poverty and environmental degradation have fueled these groups’ ability to recruit by exploiting desperation and instability.

As More Go Hungry, Children Are Most At Risk

Conflict, displacement, natural disasters: combined, they’ve left 149 million people facing severe levels of hunger. And the pandemic could nearly double that number to 270 million. Sadly, as hunger and conflict increase, children will suffer most. Kids living in a conflict zone are more than twice as likely to be malnourished than children living in a peaceful setting, and four out of every five stunted children are living through war.

If kids keep bearing the brunt of conflict, the world will face intergenerational losses from hunger and malnourishment that will linger long after disasters cede. Imagine, the number of chronically hungry people around the world is estimated to reach 840 million by 2030, and hungry children can’t build prosperous societies. The goal of zero hunger won’t be achieved if we don’t put an end to war and armed conflict.

Deema, a five-year-old girl in Yemen, has been diagnosed with severe malnutrition.

Peace Dividends

The U.N. World Food Programme uses food to foster peace before, during and after conflict. For more than 50 years, we’ve worked on the frontlines of war, saving lives and bringing hope to millions caught in the crossfires. Even in conflict-affected areas, if we have access, the worst forms of hunger – even famine – can be prevented. And our lifesaving support creates important peace dividends. For example, in exchange for food rations or cash transfers, food-insecure communities can work with us to build roads and ponds, plant trees and restore land. These Food Assistance for Assets programs reduce competition over natural resources like land and water, build social cohesion and provide economic opportunities for young people.

We know that food is a building block of life and a cornerstone of peace. It’s up to us to deliver it.

Read the full report here, and donate here to help us continue our lifesaving work.