How WFP Classifies Crises and Why COVID-19 Is at the Top

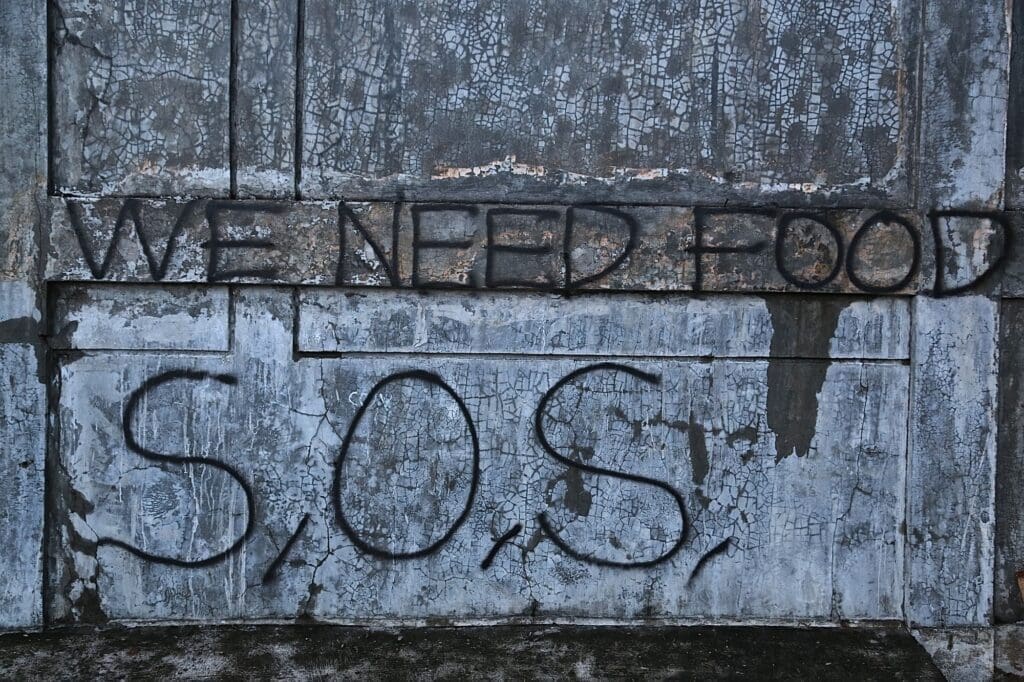

Hunger feeds on crisis. When disaster strikes, hunger often follows. The majority of the time, the crises are caused by conflict, violence, hurricanes or drought. This time, it’s caused by a global pandemic.

COVID-19 is hurting everyone, but it threatens vulnerable communities the most. In many of the countries that the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) serves, health systems are barely functioning, there is limited access to clean water and sanitation supplies are out of reach. Additionally, people are already suffering from poverty, hunger and malnutrition. As a result, the impact of the virus in these places and the economic consequences that follow will be devastating.

With this in mind, on March 30, the U.N. World Food Programme officially classified the COVID-19 crisis as an L3 emergency. But what, exactly, does this mean?

For humanitarian agencies like the U.N. World Food Programme that must respond to multiple emergencies in more than one country, a classification system is used to determine which crises require the most resources. The most severe emergencies are classified as Level 3 or L3 for short. Right now, these are the regions and/or situations that have been classified as L3:

- The COVID-19 pandemic

- Northeastern Nigeria

- South Sudan

- Syria

- Democratic Republic of Congo

- The Sahel

- Yemen

But, there are actually two types of L3 emergencies: L3 emergencies across the U.N. system—which apply to most humanitarian organizations worldwide—and corporate L3 emergencies that pertain only to a specific agency like the U.N. World Food Programme.

A system-wide L3 emergency is declared by a committee of United Nations (U.N.) and non-U.N. global humanitarian agencies to ensure that the appropriate leadership structures are put in place for a coordinated, global response to a large-scale event. This need occurs most often when a crisis changes suddenly and significantly, requiring ramped-up efforts on multiple fronts—food, health, support to refugees and so on. To make this determination, the committee considers the scale, complexity, urgency, capacity and reputational risk involved with the crisis.

Meanwhile, the U.N. World Food Programme—and other humanitarian agencies—employs its own internal emergency classification system. The U.N. World Food Programme’s process not only takes into account the complexity of a crisis, but the resources and capacity available to its country offices and regional bureaus to respond.

The U.N. World Food Programme has three levels of classifications. Any country with a U.N. World Food Programme emergency or relief operation is automatically classified as an L1. When the resources of a given country office are insufficient to meet the urgency, scale or complexity—or when the scale of crisis extends beyond a single country or territory—an L2 emergency can be activated, allowing regional resources to be utilized to amplify the response. When an emergency exceeds U.N. World Food Programme regional support capacity, an L3 designation allows the U.N. World Food Programme to use its entire global, or “corporate,” human or financial resource base to respond.

While this all sounds relatively straightforward, given the dual-track nature of the global emergency designation system, L3 classifications are not always simple to interpret. Quite simply, not all system-wide L3 emergencies trigger a U.N. World Food Programme L3 activation, and not every one of our L3 activations is considered a system-wide L3.

For example, slow-onset disasters like the El Niño-induced drought in Southern Africa that caused a U.N. World Food Programme—but not system wide—L3 emergency in 2016 may overwhelm the capacities of our country offices and regional bureaus, yet may not meet the system-wide L3 criteria for urgency, scale and complexity brought on by sudden-onset and quickly changing emergencies.

In the same way, not all system-wide L3 designations automatically trigger a U.N. World Food Programme corporate L3 classification. Instead, as long as we are able to sufficiently address humanitarian needs under the system-wide L3, we can independently classify the emergency in a manner it feels most appropriate.

In the end, the U.N. World Food Programme takes a “no-regrets” approach to its emergency classification process, preferring to upgrade an emergency to ensure urgent needs are met as opposed to under-allocating resources. As such, we can even activate an emergency-response level change preemptively, in anticipation of escalating need. This is often done to avoid crises intensifying beyond country and regional capacities to address them. This was successfully done in the 2012 Sahel drought response based on early warning information.

To someone suffering from hunger, though, U.N. classifications are of little concern. While agencies like the U.N. World Food Programme must categorize humanitarian crises to determine the most efficient and effective use of scarce human, financial and other resources, an L3 classification should not imply that human suffering is in any way lessened in L1 and L2 settings.

But the suffering that results from the coronavirus pandemic will be great. Currently 821 million people face hunger worldwide. COVID-19 threatens to push an additional 300 million into food insecurity, and 500 million people into poverty. The U.N. World Food Programme is working hard to make sure this pandemic—and the others caused by natural disaster and war—won’t push millions of the edge, by giving them the food and supplies they need to survive.