The Three Waves of Hunger: The Devastating Ripple Effects of COVID-19

How will COVID-19 have such a large impact on hunger? Chase Sova, WFP USA senior director of public policy and research, explains its threats and affects in three waves. The first wave of COVID-19 brought the developed world to its knees. The second wave will impact the world’s poorest and hungriest populations. The third wave will show us just how much we need one another.

The First Wave

For many Americans, the Coronavirus pandemic represents the first time that something we have long taken for granted feels tenuous: our own food security. What started as a rush for non-perishable foods turned into empty shelves and lines at grocery stores. And since then, the effects of COVID-19 on our domestic food system have only grown, threatening to become not just a problem of demand, but also one of supply.

Empty grocery stores shelves in New York.

Growers, processors and distributors for commercial food supply chains (think: restaurants, hotels and schools) have been retooling their offerings for retail markets. In the meantime, we’ve seen images of milk being dumped and vegetables plowed into the earth, their markets disappearing. As food processors become sick and work visas harder to come by, it’s become clear that our domestic food system is increasingly at risk.

These events are frightening to many Americans, for good reason. But they are happening in one of the most advanced economies on the planet. Although not without pain and considerable economic hardship for some, our food sector has proven largely resilient to these shocks and capable of meeting consumer demand. Combined with an expansion of government safety nets, the U.S. is poised to protect the food security of its people.

Many around the world are not so lucky. This week, we learned about the staggering global food security impact COVID-19 will likely cause: Over a quarter of a billion people around the world may face extreme hunger by year end. That is, COVID-19 may very well double the number of people facing crisis levels of food security worldwide, a number that had already climbed to 135 million at the start of this year.

A little girl suffering from malnutrition in Yemen, a country facing famine.

Most strikingly, in a time when we’ve all but considered famine a thing of the past, the virus may push as many as 36 countries into that terrible fate in the worst-case scenario, according to remarks made by WFP Executive Director David Beasley to the United Nations Security Council.

Since the outbreak, we’ve talked about the risk of this global health crisis becoming a food security crisis. The new Global Report on Food Crises and other statements from WFP confirm that this is already happening, and underscore that food must at be at the forefront of the global COVID-19 response. Without it, the health and wellbeing of tens of millions of people—and their countries—will be severely compromised, with predictable downstream impacts on global stability.

The Second Wave

So far, the effects of COVID-19 have been largely felt in the world’s most advanced economies. These places have sophisticated health care infrastructure and the ability to scale-up food-based safety net systems to prevent vulnerable people from falling through the cracks. This is not the case in many places where the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) works. Already, 49 of 54 countries on the African continent have confirmed cases of the virus.

People wait for food in Mozambique.

The second wave of COVID-19 will be more deadly and unfair than the first. What has been true of the crisis domestically will be true of COVID-19 internationally: the people who are already the least able to cope will be most exposed.

Projections for global GDP in the face of COVID-19 have gone from being scaled back to reversed entirely, with the IMF reporting an expected contraction of the global economy by three percent, on par with the Great Depression of nearly a century ago. Developing countries will see a slowdown in the export of raw materials and currency fluctuations, and oil exporters like Nigeria, Angola and Chad will see a major drop in income from trade. We’ve long known that economic slowdowns produce poverty and poverty produces hunger; this will prove no exception to that rule.

An elderly woman seeks shelter at a refugee camp in Uganda, after fleeing violence in South Sudan.

Already high levels of malnourishment, minimal coverage of food-based safety nets, and pervasive poverty are all reason for concern about the impact of COVID-19 in low-income countries. But there are still other aspects of this crisis in the developing world that will further increase the likelihood of it causing severe food insecurity.

WFP is frequently mobilized to respond separately to a supply shock (e.g., drought) or a demand shock (e.g., recession). Only in the most severe circumstances, like prolonged conflict and COVID-19, is the food system hit from both ends – and this almost never happens on a global scale. In the case of COVID-19, out-of-work urban populations (demand side) in low- and middle-income countries will be hit just as hard as small-scale farmers (supply side) unable to labor in their fields (when a small-scale farmer gets sick, no one is going to step in and manage the farm). Both will experience a loss of income and will be at the mercy of shaky food supply chains.

Only 20 percent of food supply chains in Africa and South Asia operate like they do in the U.S., with commercial farmers providing food through sophisticated channels destined for modern supermarkets. Instead, food is provided by small-scale farmers moving food through informal markets, relying on a complex network of small businesses. Food production in this system tends to be labor intensive and even subsistence-oriented, the type highly vulnerable to labor shortages from sick farmers, movement restrictions and other economic lockdowns designed to stop the spread of disease.

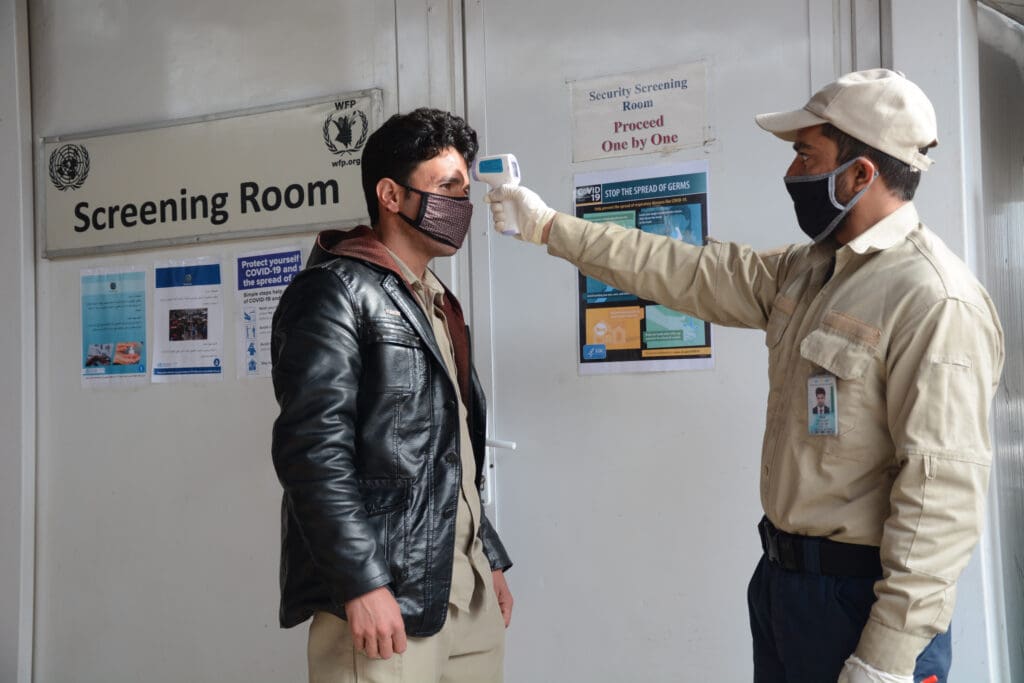

WFP mobilizing resources for coronavirus response in Afghanistan

Many of the places around the world experiencing the highest levels of food insecurity are also countries that rely most heavily on food imports. Globally, we produce billions of tons of food each year, more than enough to meet calorie needs of every man, woman and child on the planet. Yet we rely heavily on complex systems of global trade to move food from the highly concentrated places it is grown to places where it is demanded.

A small-scale farmer in Mozambique. Farmers like her are particularly at risk of hunger from COVID-19.

This is a surprisingly fragile system, with failures affecting land-locked countries especially strongly. Protectionist policies like food export restrictions have been put in place in 17 countries so far in response to COVID-19 affecting over four percent of grains worldwide. In a time of abundance, policies like these only serve to exacerbate hunger in both the countries imposing bans and those affected by them.

The good news is that this does not need to be another 2007/8 global food-price crisis. Global food stocks are sufficient to meet demand and projections for critical harvests are strong. But governments must make conscious efforts to keep their agricultural and food trading systems free and open; the laws of supply and demand aren’t bothered by human suffering, even if we are. If they do that, the global food crisis we’ll experience this year will be driven by a loss of incomes alone, not also by price spikes in critical commodities.

In Malawi, mothers wait to receive their monthly food assistance. They wash their hands before and after their visit.

The Third Wave

Conveniently, the launch of WFP’s Global Report on Food Crises coincides with the quarterly United Nations Security Council briefing on food insecurity and conflict. These two things are not unrelated. Conflict produces hunger and hunger produces conflict in a vicious feedback loop. A rapid rise in food prices during the 2007/8 global food price crisis led to civil unrest and riots in at least 40 countries and the toppling of at least one government.

We are already seeing examples of this playing out today in response to local food price spikes and shortages. What happens at the local level matters greatly as even a well-stocked global food supply won’t protect completely against local distortions and disruptions.

In Syria, women line up for WFP food using social distancing.

The third wave of coronavirus will show us that, in a globalized economy, we are only as strong as our weakest health care system and our weakest food system. There has been much talk about how a failure to address COVID-19 impacts in places like sub-Saharan Africa will all but ensure a resurgence of the virus in places like the U.S. in the months to come.

That’s true, but it is not a rebound of sickness alone that should worry us: it is the likely socio-economic and political fallout from COVID-19 in developing and fragile countries that keeps many observers up at night. Modern day crises do not respect borders. The virus will only serve to entrench conflicts we are already fighting, cement poverty we are already experiencing and lead to a greater global instability. Governments that are stretched to the limit and people with nothing to lose are both targets of groups seeking to sow the seeds of unrest.

A man has his temperature checked in Afghanistan, a country already mired by conflict.

And the destabilizing impact of the virus on world order will not be quick to pass. The losses caused by COVID-19 are likely to be intergenerational. Already, the virus has taken 1.6 billion children out of school, many of them losing access to critical school meals in the process.

WFP and other international organizations are sounding the alarm with regard to these and other COVID-19 impacts on the world’s most vulnerable people. Not since the Second World War has humanity needed to rise to such a momentous and tragic occasion. How we respond today will determine how long we will live with the consequences of this pandemic. As we mobilize that response, food must remain at the top of our agenda.