The Humanitarian Monster Truck

Humanitarian relief often comes down to the last mile, that flooded stretch of road that stands between food assistance and a desperate community. The last mile is the hiccup that can undermine an entire operation, its size no indication of the trouble it can cause.

Buzi, a rural area in northern Mozambique, was isolated after Cyclone Idai. Surrounded by water on all sides, homes were flooded for seven days and a high proportion of farms are still submerged. Families waited for emergency assistance in treetops, some for up to three days. Grain storehouses were flooded. Livestock drowned or escaped to higher ground.

Sherps can drive through deep water and carry one ton of food.

For the first two weeks following the cyclone, some 100,000 people received World Food Programme (WFP) assistance from helicopters and boats only. But when that many people need urgent help, trucks are the fastest, cheapest way to get it to them.

Two WFP trucks set out for Buzi on 4 April, but the dirt road was so waterlogged that the first truck sank, unable to move forward. When the second attempted to drive around, both vehicles fell together like playing cards, touching at the top. Lighter and faster, a 4×4 in the convoy tried to pass, but only got as far as the front of the pile-up. Instead of bringing relief, the convoy itself had become a blockade.

For the first time in a sudden-onset emergency, WFP had a new option: an amphibious truck, like a tank with inflatable wheels, called a Sherp — a name that suggests the fortitude of one who scales Mt. Everest loaded with a pack.

“It’s like a humanitarian monster truck,” explains Adam Marlatt, an expert on mission with WFP, who sat in the passenger seat.

“It’s like operating a forklift,” says driver and Regional Fleet Manager, Nobuyoshi Kida.

After field-testing two Sherps in the Democratic Republic of Congo and three in South Sudan in 2018, WFP included two of the Ukraine-made vehicles in the response to Cyclone Idai. “This is a cost-effective supply chain innovation that goes directly to the target — the population in need. We are changing the idea that we have to use a helicopter or an airlift,” adds Kida.

Shortly after the trucks got stuck, two Sherps arrived from Beira on the back of a flat-bed truck to solve the problem of the blockade and get supplies to Buzi. Before the Sherp could proceed, however, crucial navigational information was needed. Sherps can’t climb a vertical wall, so the driver needed to know where the slopes tapered off. It was also imperative to avoid rapids that could push the vehicle towards the Indian Ocean.

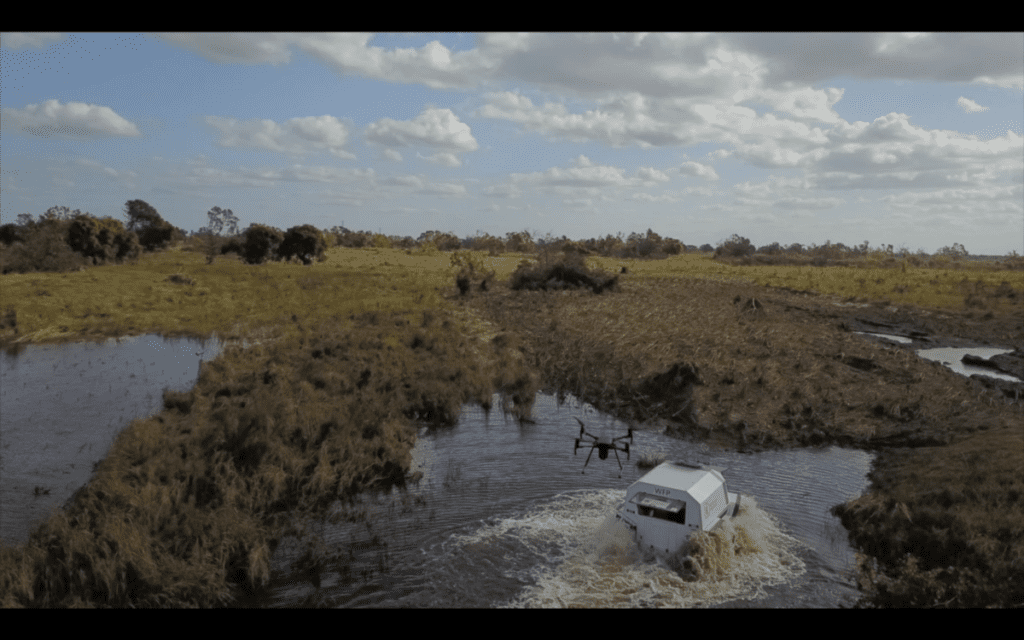

A drone was sent up for a bird’s eye view of the area.

A drone allows the sherp driver to chart a safe path through the deep water.

Images from the drone, piloted by Marlatt in the passenger seat, were broadcast onto his phone screen, so he could ‘see’ past the tree tops and the swamp, and was able to navigate the remaining 30 kilometers to Buzi.

“It’s interesting to pair an emerging solution in the logistics world like the Sherp with an emerging solution in the tech world, like drones. The two complement each other,” reflects Marlatt.

In the following 48 hours, 26 metric tons of food were moved into Buzi, one ton at a time, the drone leading the Sherp across the unpredictable river.

The Sherp allowed WFP to reach isolated communities without resorting to costly airlifts.

Once the operation in Buzi was completed, the amphibious vehicles were moved back to Beira, ready to assist in the next flooded area. With two Sherps warehoused in the Southern Africa region, WFP and the Mozambique National Institute of Disaster Management (INGC) now have more cost-saving options for reaching stranded populations.

WFP has reached 1.3 people hit by cyclone Idai in Mozambique and is now responding to a new emergency caused by cyclone Kenneth. Learn more.

This story was written by Tej Rae and originally appeared on WFP’s Insights.