Rethinking Packaging, Reducing Waste

At the current rate of solid waste production, experts agree, the world is heading for environmental disaster. Rethinking the ways we produce, package and consume goods is becoming a moral, as well as economic, imperative: we are urged to reduce food waste and the use of single use plastic, reuse what we can and recycle what can no longer be used. But what does this mean for an organization like the World Food Programme (WFP), which on a daily basis delivers food — bags of cereals and pulses, bottles of vegetable oil, boxes of biscuits, sachets of nutrient-rich special foods — to millions of people across the world?

In 2017, WFP distributed 3.8 million metric tons of food in 71 countries.

“When you work to save and change the lives of millions of people, doing it in a way that causes serious harm to the environment would be counter-intuitive,” says Thibaut Mirieu de Labarre, Packaging Expert at WFP.

While packaging might not be the first thing that comes to mind when thinking about WFP’s work, it plays a pivotal role in preserving the safety and quality of the food delivered to people in need, and preventing waste so that even more can be reached.

“Our choices are dictated by the need to ensure not only that our food is safe — that it does not harm those who receive it — but also that it keeps its qualities intact, so that it provides people not just with the calories they need to survive, but also with the nutrients they need to thrive,” Mirieu de Labarre continues.

This is no small feat considering that the life of WFP food is nothing short of adventurous: it travels long distances by air, sea and land; it has to withstand high temperatures both in storage and during transport; and in extreme cases — when all other avenues are closed, including during sieges — it can be dropped by an airplane.

Hundreds of displaced families in Ganyiel, South Sudan await a lifesaving airdrop of food from WFP.

Additionally, packaging must respond to the needs of users. “The people we serve are at the heart of our work — we try to understand their needs and habits, and we look at what is best to safeguard their dignity and humanity,” says Mirieu de Labarre.

For example, WFP is looking to reduce the size of the bags in which it distributes Supercereal — a nutritious supplement used to fight malnutrition — so that they are easier to transport, and has changed the packaging of its lipid-based nutrient supplement from weekly rations in pots to daily rations in sachets.

WFP reduced the size of PlumpSup’s packaging, making it possible to deliver 12% more food in the same amount of space.

“The sachets are easier for the mothers to use, making sure that the children receive the right amount of nutrient-enriched food, and preserve the hygienic conditions of the food in situations that are often very precarious,” Mirieu de Labarre explains. The change also had other positive impacts: it brought down transport costs — 12 percent more rations could be transported using the same space — and reduced product and packaging waste.

In real terms, packaging only represents at most 5 to 10 percent of the environmental footprint of any given product through its full life cycle — thus making it crucial to also reduce the impact of food losses and transport along the supply chain. However, in light of the size of WFP’s operations, the impact of packaging cannot be disregarded.

“Whenever possible, giving the difficult conditions in which we operate, we look at packaging waste management through the well-known 3R lens: reduce, reuse, recycle,” says Mirieu de Labarre.

For WFP, reducing can take many different forms — from using fewer colours on packaging so as to avoid ink pollution when discarded, to optimizing the thickness of cardboard boxes, or considering removing the metallic layer used in plastic films to prevent the release of toxic fumes if burnt.

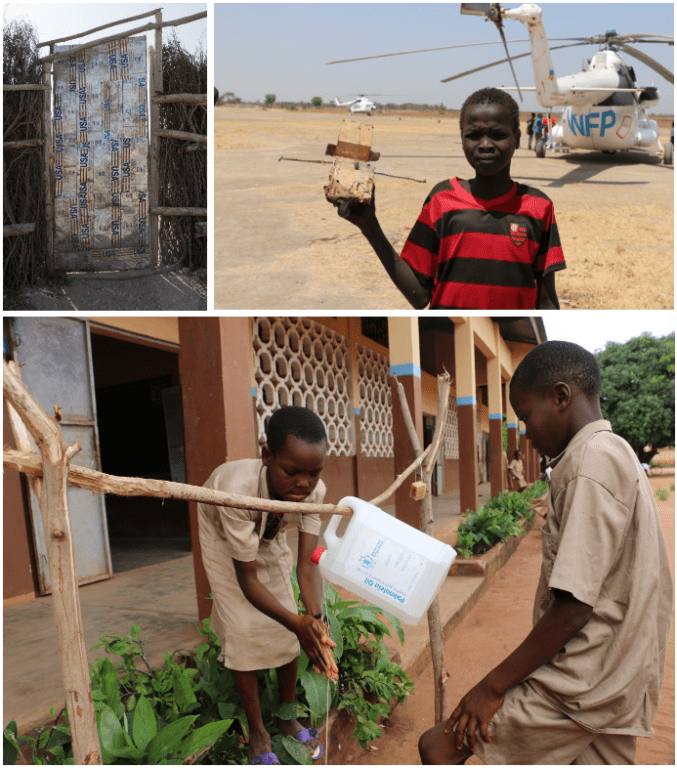

Taking into account that people are already widely reusing WFP containers — bags and jerrycans to transport other items, the metal from vegetable oil steel cans to build shelters — WFP is keen to use materials that are safe for them. “We are going beyond that — looking at how we can design the packaging with reuse in mind from the start. We are thinking of cardboard boxes that can then be used to grow vegetables, or that will have reuse suggestions printed on them, so that, for example, they can be turned into furniture or toys,” Mirieu de Labarre explains.

People reuse packaging to build homes, create toys and wash their hands.

“We also want to educate communities to see value in packaging and give them the tools and means to realize this value,” he adds.

And of course, whatever does not find a second life, should not just automatically head for the landfill. Recycling initiatives, promoted by different organizations — including UN agencies — are happening in many of the places where WFP works.

“The key is a coordinated approach. All aid agencies share the same challenges. We are looking for ways to come together to share waste management best practices as well as local initiatives. Collectively, the waste we produce can reach the critical volume to make recycling it an interesting business for private sector partners. Sustainability offers a perfect opportunity for partnership and collaboration,” Mirieu de Labarre concludes.

WFP works with private sector and academic partners — including for example packaging manufacturing leader Amcor and the University of Amsterdam — and donors like USAID to develop solutions that minimize losses, optimize costs and reduce the environmental impact of its packaging. As WFP increasingly sources its food from local suppliers in developing countries, where laws and regulations may not be as well developed as in the global north, it provides support and training to food producers and packagers so that they can comply with WFP’s standards for safety and sustainability.

This story was written by Simona Beltrami and originally appeared on WFP Insights.