Inside the High-Tech Tool That Tracks Hunger Crises and Helps Us Save Lives

To mark World Creativity and Innovation Day, we are taking a look back at our conversation with Jonathan Rivers, head of the United Nations World Food Programme’s mobile Vulnerability Analysis and Mapping (mVAM) initiative – now known as the Hunger Monitoring Unit.

Since its beginning, the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) has relied on data collection to get the information it needs to reach hungry people. But collecting primary data on households’ food security can be challenging at times ‒ particularly in areas with limited humanitarian access. So in 2013, the U.N. World Food Programme piloted the mVAM project to harness mobile technology towards remotely monitoring household food security and food market-related trends in near real time.

This capability was critical when COVID-19 hit, and the Hunger Monitoring Unit has continued to ramp up its capacity to meet the increasing need. The project’s data collection has also enabled us to observe the effects of extreme weather on the livelihoods we serve. When Hurricanes Iota and Eta tore through parts of Central and Latin America in late 2020, we were able to immediately see the impact on the food security situation and deploy emergency assistance to those hit the hardest by the storms.

Curious to learn more about the mVAM initiative, we dialed up Jonathan Rivers, head of the hunger monitoring unit at the U.N. World Food Programme, in July of 2020.

***

World Food Program USA: Thank you for joining us, Jonathan. Can you tell us a bit more about how mVAM started and how it works now?

Jonathan: Sure. When we originally launched mVAM, we used it to collect data through people’s mobile phones, using text messages, voice calls, etc. Through those experiences, we tried hard to figure out what the best approaches to reaching people through this technology might be.

Jonathan Rivers, head of the U.N. World Food Programme’s hunger monitoring unit.

There were a lot of lessons learned. Over the years, mVAM has evolved a lot. We’ve come to understand best practices for using this technology at scale, and address some of the obstacles we’ve come across.

Timing is one of those obstacles. The more quickly we could collect data, the most effective it was. So, we evolved mVAM into what the near real-time technology it is today. It helps us quickly identify changing food security situations in vulnerable countries. We do this by collecting data from a call center, processing it, analyzing it and then displaying it in about 24 hours. So basically, mVAM now enables us to track the food security situation in more than 29 of the most vulnerable countries on a daily basis.

World Food Program USA: You mention using technology, like text messages, typically associated with mobile phones. The U.N. World Food Programme works in some difficult places. How do you use mVAM when there isn’t access to mobile phones, or maybe even internet?

Jonathan: We have a variety of ways of dealing with the bias that’s introduced by only being able to reach people who have access to these technologies.

The first thing we do is to set up a methodology that makes it geographically representative of a country’s population’s as possible. To ensure this, we produce daily dashboards that show us which parts of a country we’re not sufficiently reaching. This enables us to determine whether or not the population we are reaching is representative.

A woman in the DRC responds to a mVAM phone survey. The operator asks her questions about what she and her children have been eating over the last seven days, and how they have been coping if short of food.

We also deal with it mathematically through something called propensity score weighting. This formula enables us to determine if our population looks substantially different than the population we should be reaching, and thus, if we need to readjust to reach a more accurate conclusion. But, there’s always going to be people and places we can’t reach. We try to be as transparent about that as possible because if people misinterpret our data and take the wrong information from it, they can do some harm.

World Food Program USA: With COVID-19, it seemed like everything changed overnight. In an emergency like this, mVAM must be critical to helping the U.N. World Food Programme reach people. How did you adapt this program in light of the pandemic?

Jonathan: In this situation, the U.N. World Food Programme was lucky as we’ve always invested in putting these systems in place. So, when we entered this crisis, we were already collecting data continuously in 15 countries. And in these countries, we could see clearly how food security was reacting in the first few weeks of restrictions, and this helped the U.N. World Food Programme prepare.

The U.N. World Food Programme, with the Government of Uganda, distributed take-home rations to school children in northeastern Uganda to support families while schools remained closed due to COVID-19.

Food security shocks happen all the time, but we realized there were aspects of this shock that were fundamentally different from others. We decided our data needed to monitor those unique challenges that came with it – like supply chain disruptions and household access to healthcare and markets. We also wanted to look more at how pandemic response was impacting people’s livelihoods. So, we modified the questions we were asking to get the information we needed to properly respond.

Thankfully, we were able to do this within a few weeks from the official pandemic declaration, because we already had this technology working in 15 countries. Our next goal was to scale up quickly to monitor 40 countries – and we’re already at 29.

WFP USA: It sounds like because this system was already well built, you were able to respond and adapt quickly to meet the changing circumstances. Did you encounter any challenges during this process?

Madonna Kanisio is the mVAM focal point in South Sudan. She collects household food security data through an in-house call center. At the end her collection period, she downloads the data from the server to analyze different indicators and keep an eye for trends and changes over time.

Jonathan: Yes. We use call centers to collect much of our data, and as non-essential businesses, they were among the first to shut down. It threw a major obstacle in our path, but thankfully, through the relationships we’ve built, we were able to ensure that call center staff were fully equipped with the technology they needed to keep doing this job at home. We haven’t had any problems since then, but it was an interesting challenge we didn’t anticipate ever having to solve.

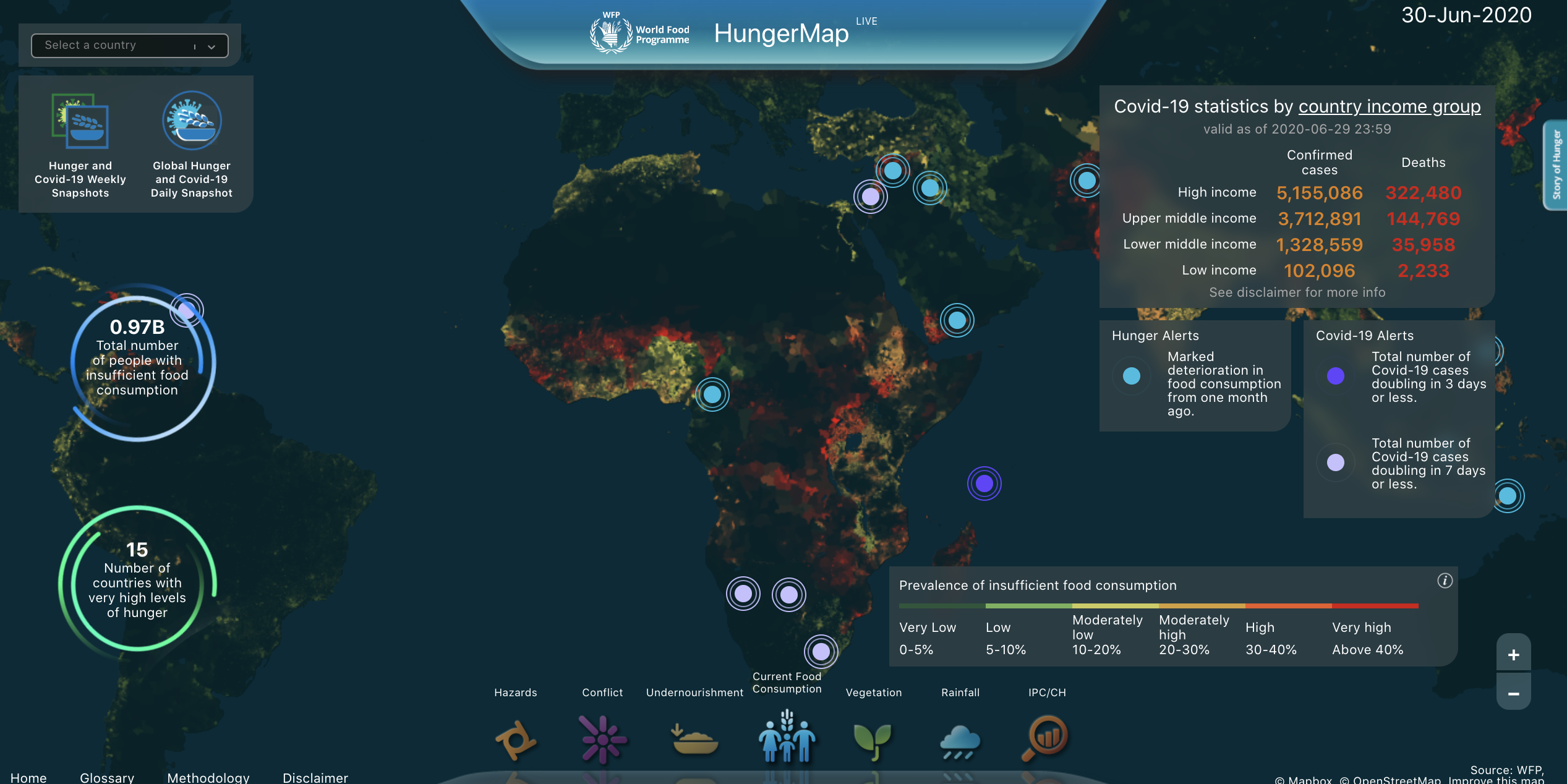

World Food Program USA: At World Food Program USA, we frequently use HungerMap LIVE, a visualization platform for the data you collect. Have you adapted HungerMap LIVE to reflect the new information you’re collecting in light of COVID-19? And have you added any other features during this time?

Jonathan: We’ve updated it quite a bit to reflect the new data we’re collecting. It now includes a daily snapshot of COVID-19 impacts. It shows the rates of increase in country income groups, how many cases and deaths there are in the regions where the U.N. World Food Programme operates and points out the 20 countries that have the fastest doubling rates of COVID-19. It then juxtaposes all of this with an aggregate view of the hunger situation in these areas, to demonstrate how they connect.

HungerMap LIVE updated with new data in light of COVID-19.

World Food Program USA: Do you have any examples of how the U.N. World Food Programme and other organizations are using this new information to make decisions?

Jonathan: Sure. Most U.N. World Food Programme country offices have embraced the information we’ve secured on the impact of livelihoods and market functionality, which looks at different markets in various countries and how they’ve been impacted by supply chains. This has been really useful for them in tracking in food security and preparing to meet an increasing need.

I would say the biggest users of the data is the Global Food Security cluster – a group that coordinates with partners globally to enhance food security. They are putting together monitoring frameworks to enhance humanitarian response, and they’ll be relying heavily on our data to do so. mVAM will help them monitor the risks COVID-19 is posing to certain countries and provide them with baseline numbers that will help in assessing impact.

David Beasley, executive director of the U.N. World Food Programme, met with the president of Panama, Laurentino Cortizo Cohen for a Humanitarian Response Depot ribbon-cutting ceremony in Panama City.

We also have a lot of interest in mVAM from governments that want to access the data – particularly our data on livelihoods – to support their decision making in this crisis. There’s been a lot of interest across the board.

World Food Program USA: As you look at the way mVAM is being used in this pandemic, are there any takeaways that will change the way you operate going forward? Has it caused you to re-think your priorities or vision for mVAM in the future?

Jonathan: One of the biggest lessons learned is the importance of being prepared so that systems are up and running in case of disaster. mVAM technology was already in place, so we were in a position to quickly collect and distribute information critical to meeting the changing food security needs and help the U.N. World Food Programme save lives.

Now, what we have to do is scale this system up, so it’s running in all the countries the U.N. World Food Programme serves. We also have to ensure that we always have partnerships, platforms and resources in place to mobilize quickly, in case a crisis like this happens again.

Members of the WFP mVAM team working on HungerMap LIVE.

WFP USA: We have one more question before we wrap things up. Through all your work with mVAM and the U.N. World Food Programme, has anything about this technology and its impact surprised you?

Jonathan: Certainly. I’m continuously amazed at what we can accomplish through these technologies and the number of people we can actually reach – even in some of the most difficult parts of the world. In just the past three years, I’ve seen connectivity increasing more quickly than most people realize. This shows us how much is possible and empowers our team to keep striving to make mVAM better. This technology is already helping the U.N. World Food Programme save millions of lives, so just imagine how much more of an impact it can have in the future.