How to Win the World Food Prize: Lawrence Haddad’s Work in Global Nutrition

Each October, The World Food Prize is awarded to a person or people who have made outstanding contributions to improving the quality, quantity or availability of food in the world. It’s the foremost prize in its field, and for the past 30 years, has recognized people from across the world at its ceremony in Iowa.

In 2018, Lawrence Haddad, along with David Nabarro, won The World Food Prize for their leadership in elevating maternal and child nutrition to the global agenda. Lawrence has a long career in food and nutrition, and currently serves as the executive director at Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition, better known as GAIN.

As this year’s World Food Prize ceremony nears, we thought it would be a good opportunity to sit down with Lawrence to learn more about the incredible work that led to his recognition – and how he hopes to change the world

WFP USA: You’ve had a long, prestigious career driving the global nutrition agenda. Looking back, when did you first get excited about global food and nutrition security?

LH: I started getting interested in the topic as early as my undergraduate days. At 18, I could not decide between science and economics and so I found a course that was exciting because it focused on a new and emerging field in the late 1970s—food technology—but also included the economic side of things (BSc. in Food Science and Food Economics at University of Reading, UK).

For me, these two subject areas, food science/nutrition and agricultural economics, have always seemed like natural partners, and so for the next 40 years I tried to get the rest of the world to see that these communities needed to work together to nourish the world sustainably.

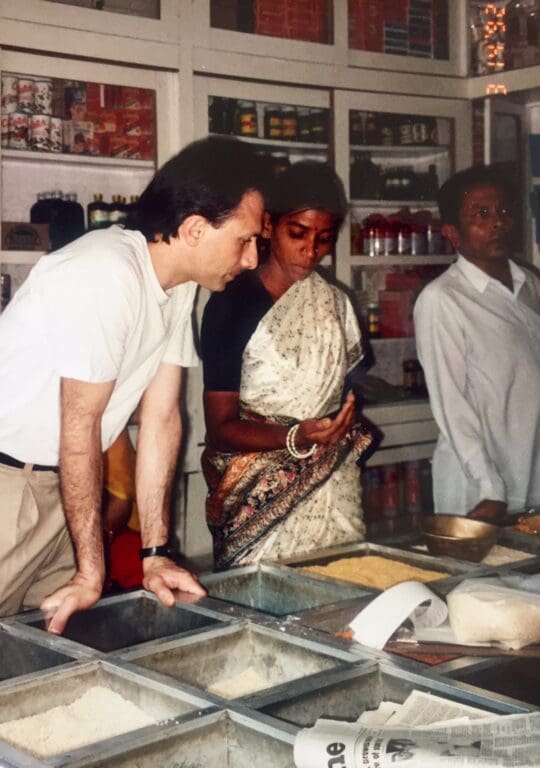

Lawrence Haddad looking at food prices and food availability in Aurepalle, Andhra Pradesh, India in 1992.

WFP USA: What did it mean to you to receive The World Food Prize last year? And how has that platform has helped to bring further visibility to your goal of global nutrition security?

LH: For me it was an important moment of recognition for nutrition from a community that thinks more about food production and hunger, and so it was really meaningful. It made it feel like the agenda that David and I and others have been pursuing – repositioning nutrition – has been recognized within a wider world. The Prize has helped me to reach into other domains that we absolutely need to build alliances with to end malnutrition—businesses, climate activists and private investors.

WFP USA: There seems to be a convergence between agriculture and nutrition communities that hasn’t always existed. How has the role of nutrition on the international aid agenda evolved over time?

LH: It’s a big question, but nutrition has gone from a being seen as a minor health outcome to being seen as a “marker” and a “maker” of sustainable development. It is a marker, because if people are malnourished, development is failing, and a maker because, unless people are well nourished, they and their societies and economies cannot realize their full potential.

WFP USA: Can you talk about the origins of GAIN? What were the motivations for the global community coming together to launch this important platform in 2002?

GAIN was established in 2002 to help scale up large scale food fortification. Billions of people do not eat enough foods that contain the micronutrients vital for development and growth, so adding them to foods that people regularly consume – for example, wheat, maize, rice, cooking oil, salt— at the point of milling or minimal processing will help prevent manifestations of micronutrient deficiency.

A school meals cook in India holds rice fortified with vitamins and minerals – like iron, zinc and vitamin A.

There is still a huge unfinished agenda, but over the past 17 years, GAIN has helped to make fortified foods available for over 1 billion people. Our goal is to reach another 1 billion by 2022, working with our many partners. The fortified staple food coverage we are achieving right now is about 250 million people per year, so we have to do a lot in the next three years to meet our ambitious target, and we are looking for help!

GAIN’s overall goal is to sustainably improve the consumption of safe nutritious foods for all, especially the most vulnerable, and we do this in a variety of ways in addition to large-scale fortification: via consumer demand creation for nutritious foods, developing data and tools that allow others to make food systems more nutritious, piloting nutritious food interventions for children, adolescents and workforces and embedding them within government national and provincial programs, and by supporting small and medium enterprises producing nutritious and safe foods to grow and transform their national and local food markets and food systems.

WFP USA: How have you worked with WFP in the past, and how can you work together in the future to improve nutrition worldwide?

LH: WFP is an important partner in all of this, providing a vital platform for distribution, creative ideas about building markets and being a key champion of the need to improve the consumption of safe, nutritious food. One of WFP’s former executive directors, Catherine Bertini, is now GAIN’s board chair and GAIN and WFP co-convene the SUN Business Network which supports the 61 countries in the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement to work with business. So, the ties between the two organizations run wide and deep.

WFP USA: In addition to humanitarian agencies playing a role, what role can the private sector playing in improving nutrition – especially among some of the most vulnerable populations?

LH: Most people, even the most vulnerable, buy significant amounts of food from markets, and behind these markets are a vast array of businesses. So, if we want businesses to play a complementary role to governments in providing access to affordable safe nutritious food, we have to find ways of incentivizing them to do so. These ways can include subsidizing the production and processing of certain foods, de-risking private investments in small and medium enterprises, and building the demand for nutritious foods and food products.

I would like GAIN to work more closely with WFP on food systems in fragile contexts to build on WFP’s interesting work using food aid and cash transfers to build local food markets, thereby enhancing aid recipients’ choice and dignity as well as building resilience.

A woman selling greens at a food market Democratic Republic of Congo.

Photo: WFP/Deborah Nguyen

WFP USA: Why does global nutrition security matter – not only for people who are malnourished, but for all us, in the U.S. and worldwide?

LH: Global nutrition matters because it drives most of the Sustainable Development Goals. Good nutrition:

- promotes child survival (45 percent of under-age-3 mortality is linked to malnutrition);

- promotes brain development, which results in greater school achievement, better labor market outcomes (wages, retention, productivity), greater entrepreneurship, lower poverty and higher national income;

- prevents diet-related chronic disease later in life (such as obesity and type 2 diabetes);

- helps mitigate climate change (as people eat more fruits vegetables, legumes, nuts, fewer greenhouse gases are emitted); and

- lowers the cost of universal health coverage because poor diets are responsible for 20 percent of premature adult mortality.

A child in Laos with a nutritious school lunch provided by WFP.

WFP USA: What do you see as the next frontier in global nutrition security? We’ve seen great progress, but what remains to be done?

LH: The key frontier is, “How do we make nutritious diets available, affordable and desirable for all people, especially the most vulnerable?” It is the next frontier because nutritious food is out of the reach of most people on the planet. And healthy diets unify communities that care about nutrition, climate, environment, biodiversity and entrepreneurship – so a focus on healthy diets is politically powerful.

From a health perspective, access to nutritious food is at the heart of preventing all forms of malnutrition: stunting, wasting, anemia, obesity, type-2 diabetes etc., and for too long we have seen the consumption of such foods simply as a matter of consumer choice. The truth is most consumers find it very hard, if not impossible, to make healthy choices. If they have enough money, they have too little information, time or choice at point of purchase to make a healthy decision, and if they do not have enough money they are forced to eat staple foods that are low in micronutrients and snack foods that are very cheap but high in sugar, salt and trans fats.

Transforming businesses from being a big part of the problem to a big part of the solution is that key challenge that GAIN is taking on in this frontier. How can governments incentivize and support businesses to produce and promote more affordable nutritious foods? This is what keeps me awake at night and drives us on at GAIN.

A woman looks over her produce at a market in Somalia.

WFP USA: Looking back through your career, you’ve had a tremendous amount of accomplishments. What are you most proud of and why?

LH: It is really hard to say. I am tremendously proud of what GAIN is doing, being brave enough to grasp the nettle of figuring out how public private engagement can advance nutrition.

Overall, I am most proud of my contribution (along with hundreds of others) to making people think differently about nutrition and act differently as a consequence. When I joined International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) in the early 90s, most of the economists there thought that nutrition status was just a nice bonus outcome of important work on improving agricultural productivity. Now, they see nutrition is a primary outcome and, more importantly, as a primary input into achieving agricultural transformation. We have flipped the paradigm on its head—now Ministers of Finance increasingly see child growth as the foundation for economic growth. And that is as it should be.