How Extreme Weather Is Pushing More People Into Hunger

Cyclones Idai and Kenneth highlight the impact of extreme weather on food insecure communities — and the need to act early using forecasts and contingency plans.

The two devastating cyclones that have hit Mozambique in the space of just over a month seem to confirm something climate scientists have been saying for a while: the weather is becoming more unpredictable, and extreme events more frequent.

It is unprecedented for two tropical storms of such strength to hit the country in the same season — let alone so close to each other — and to make landfall in areas that are not traditionally prone to cyclones.

Mozambique, however, is not alone. Climate events currently account for 80 percent of all disasters recorded globally. According to a 2018 report released jointly by five UN agencies, the number of weather extremes, including extreme heat, droughts, floods and storms, has doubled since the early 1990s. An average of 213 of these events have occurred every year between 1990 and 2016.

A Disturbing Trend:

- Floods, like those experienced in Mozambique in the wake of the two cyclones, cause more climate-related disasters globally than any other extreme weather event.

- The occurrence of flood-related disasters has increased 65 percent over the last 25 years.

- The frequency of storms is not increasing as much as that of floods, but storms are the second most frequent driver of climate-related disasters.

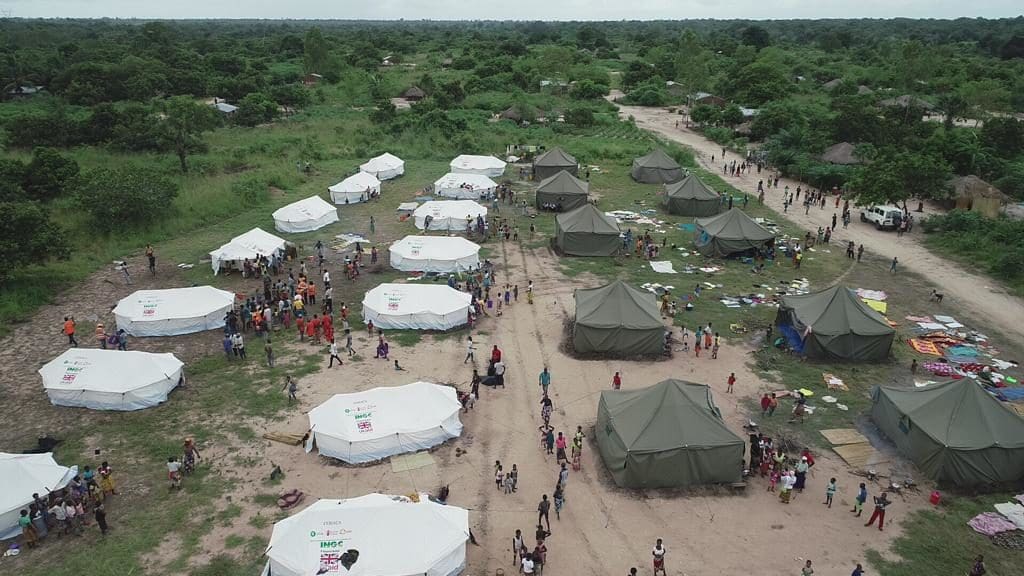

An emergency food distribution in Bandua, Mozambique keeps the 20,000 people of this small town fed. They’ve been isolated since cyclone Idai, as the roads are cut-off by water. Leaders say all their crops have been lost and many people are suffering from malaria.

Recent studies have found increasing evidence that climate change is making specific events more likely and more damaging, and three things are clear:

- Climate variability and extremes are already threatening the food security and nutrition of millions worldwide.

- They affect people’s ability to access sufficient quantities of nutritious foods at all times, thus contributing — alongside conflict — to the recent new rise in world hunger.

- Evidence shows that in countries highly exposed to weather extremes, the number of undernourished people has more than doubled compared to those that aren’t.

A possible solution

“The impact of cyclones Idai and Kenneth shows how countries and humanitarian organizations need to invest in early warning and disaster management systems. These systems will help us identify and prepare for tropical storms, and act early and decisively to protect vulnerable people and infrastructure,” says Gernot Laganda, Chief of Climate and Disaster Risk Reduction at the World Food Programme (WFP).

“Setting up forecast-based financing systems for floods and cyclones could reduce the damage caused by these events in the future,” he adds.

Forecast-based financing projects can reduce the scale and costs of a humanitarian response. WFP needs $148 million dollars to deliver life-saving interventions for the next three months.

Forecast-based financing is a risk management approach developed between humanitarian actors and national disaster response agencies. A forecast triggers timely anticipatory actions when a natural hazard is likely to exceed a specified ‘threshold’ — or level of impact.

In the case of storms or floods, these can include distributing cash to poor families in disaster-prone areas so they can buy food and supplies before roads or markets are closed, establishing safe storage for food and livestock as well as identifying evacuation routes. Clearly-defined operating procedures linked with pre-agreed funds ensure that these actions are implemented before hazards turn into major disasters. This allows governments and humanitarian partners to take advantage of the window of opportunity between the early warning and the disaster occurring and to mitigate the severity of its impact.

In Nepal, the forecast-based financing approach has been piloted for river flooding since 2015. Anticipatory actions have been designed at the community and government levels and early warning lead time has been increased from merely a few hours to a couple days. The approach was included in Nepal’s Strategic Action Plan for Disaster Risk Reduction and Management 2018–2030, as well as in the target district-level disaster response plans with budget allocations for implementing anticipatory actions in response to an early warning.

“Forecast-based financing projects can reduce the scale and costs of a humanitarian response, while also improving the coordination between governments, communities and humanitarian organizations,” Laganda explains.

While these flood and storm forecast-based financing mechanisms were not in place to support communities and minimize the damages before the cyclones hit Mozambique, Malawi and Zimbabwe, this approach is not totally new in Mozambique.

“Together with the Mozambican and German Red Cross, WFP is identifying anticipatory actions that strengthen early responses to storms by the national disaster management and social protection systems,” Laganda concludes, stressing the high potential of this collaboration, both in Mozambique and elsewhere in the world.

This story was written by Simona Beltrami and originally appeared on WFP Insights.

Our hub for all things related to the cyclones in Mozambique show just how quickly WFP responds when disaster strikes.