How Do You Stop a Slow-Motion Disaster?

Just over a year ago, the World Food Programme (WFP) sounded a global alarm about a troubling situation unfolding in southern Africa.

On that day, the region joined the ranks of some of the most troubled hunger hotspots in the world: Syria, Iraq, South Sudan. But this time, the suffering wasn’t due to conflict. It was because of drought—the worst in more than three decades.

WFP/Mashour Al-Halawani

Halfway across the world, I sat at my desk in Washington, D.C. I scanned the countries that were listed under a state of emergency: Lesotho. Madagascar. Malawi. Mozambique. Swaziland. Zambia. Zimbabwe. Only a few names left a discernible impression.

Eight months later, I traveled to one of those countries—Mozambique—on my first field mission for World Food Program USA. I thought I would see large swaths of barren land, thin herds of livestock and dramatic signs of hunger. But just one day after I arrived, those preconceived notions were shattered.

Sitting across from Michele Mussoni, WFP’s Emergency Coordinator, I furiously scribbled notes as he described the status of the relief operation. At one point, I looked up from my notepad—my pen, stopped in its tracks.

“At the end of this month,” he told me, “the emergency is over.”

Back from the Brink

The transition out of emergency is a success story not highly visible in today’s headlines. As looming famine threatens the lives of millions of people in the Middle East and Africa, intractable conflict and the resulting refugee crisis have dominated appeals for humanitarian assistance.

Over three weeks time, I started to piece together what had brought Mozambique back from the brink of disaster: The grit of women farmers; a dogged humanitarian response from WFP, bolstered by its government and NGO partners; and the return of rain, a long-awaited assist from Mother Nature.

Feed a child going to bed hungry today and be part of the success story

The country’s proximity to the Indian Ocean has made ports like Beira a major hub for regional commerce. But in recent years, some of its gifts—its waterways, its coastline—have heightened the country’s vulnerability to the effects of El Niño and a changing climate.

“Mozambique is one of the countries that is most affected by climate change” said Karin Manente, WFP’s country director. “Many of the big rivers end up here, coming from Zimbabwe, Zambia, the lakes in Malawi. It’s also a country with a huge coast. There are floods and cyclones, not just droughts.”

In the leadup to last year’s crisis, erratic rainfall, above-average temperatures and delayed planting contributed to a plummet in food production. This hurt many of the country’s farmers—80 percent of the population—who depend entirely on rain-fed agriculture. And one of Mozambique’s most popular staple crops—corn—is not resistant to drought.

“The rainfall pattern is not as predictable as farmers have been used to over the years, decades, even centuries,” Manente told me in the capital Maputo. “Here it’s been late; in some locations, it’s dispersed. Farmers have to manage that in ways they didn’t have to before.”

This time last summer, the effect of several consecutive seasons of poor harvests across south and central Mozambique converged with the worst drought in southern Africa in more than three decades.

Farmers watched their stalks of corn shrivel in the sun. Tens of thousands of children were forced to drop out of school to help put food on the table. Widespread shortages caused the price of corn grain to double from the previous year in hardest-hit areas like Gaza province.

Meanwhile, the depreciation of the national currency meant the cost of imported foods like rice and cooking oil was increasing as incomes were falling. The result: More than 2 million people needed immediate food assistance, and the annual lean season—when food stocks run out between harvests—was just three months away.

The story of what happened next—a massive humanitarian response led by WFP— is a remarkable glimpse into the realities of life on the front lines of climate change and hunger. It comprises a series of twists and turns that show how farmers in a country rich with natural resources are trying to survive amid the unpredictability of a changing climate.

Ivone’s Way Out

I met Ivone Francisco Timane in Magude, a rural area in Maputo province. She remembers when the first rains of the season fell from the sky in December of last year. A mother of six, she has lived there for all her life—43 years. Her husband, unemployed, lives at home.

“We were happy,” she said, anticipating the fruits of her green harvest. “We finally could have vegetables and grow corn seeds and watermelon.”

Magude was one of the worst drought-affected areas. Many families lost large amounts of cattle due to lack of pasture and water. WFP monitoring confirmed rising grain prices. One man told me people became sick after drinking from pools of dirty water left over from the irrigation of large sugarcane plantations. Unlike the large sugarcane fields I saw on my drive from Maputo to Magude, no irrigation infrastructure supported farmers like Ivone.

Across districts like Magude, WFP responded to the crisis as the lean and rainy seasons neared. Food for Assets initiatives gave farmers food in exchange for time spent working on community development projects; emergency school meals programs encouraged kids to return to the classroom for a hot meal; and the most vulnerable, including the elderly and disabled, received monthly food distributions.

In September 2016, WFP reached roughly 100,000 people in need. Over the next five months, WFP scaled up its assistance to reach almost 750,000 people in February 2017—the height of its emergency operations. The aid included nutritional treatment for children under five and pregnant and lactating women living in districts with high rates of malnutrition.

Back in Magude, Ivone joined 18 other women and five men to work on a WFP-supported project to prepare their community for a future of extreme, unpredictable weather. The project—planting drought-resistant cassava and sweet potato seedlings—was selected by community members and was tailored to the area’s unique landscape and biodiversity as one of 40 geo-ecological zones in the country.

Ivone and her neighbors started small, planting the seedlings on little more than one acre of land. Each day they began work at 6 a.m, tending the plots with water. As the field produced, they started a second one, making grooves in the dirt to replant new seeds.

The resulting bounty fed the workers and was also distributed to the surrounding community, thanks to the help of WFP’s partner ADRA, a humanitarian group active in Mozambique since 1987. They also learned how to make juices, cakes and soups from the highly nutritious, orange-fleshed sweet potato to sell on the market—adding value and future income from their hard work.

“We want to create an association so we can remain resilient to some of these changes in the climate,” said Saulina Antonio Sumbane, another woman participating in the project. “We can create a fund to buy food if there is another drought, to buy whatever the community needs.”

The Last Mile

By early 2017, the rainy season had brought some relief to the community of Magude. But it had also brought misery and failed expectations to other areas of the country.

In certain districts across Gaza province, heavy rain turned into flooding that washed away dirt roads, making food delivery impossible and cutting off some communities from humanitarian assistance for two to three months. In February, tropical cyclone Dineo unexpectedly made landfall on the shores of Inhambane province, destroying crops in areas already experiencing food insecurity.

These conditions and periodic funding gaps tested the momentum of the ongoing recovery effort and WFP’s ability to transport and source food. Schools participating in emergency school meals programs relied on prompt deliveries, making potential “pipeline breaks” of food a regular concern. Food purchased by WFP from Zambia often came by road, and many countries competed for Zambia’s surplus. The floods also complicated so-called “last-mile deliveries”— food dropoffs at distribution points located off the beaten path, distant from reliable public infrastructure.

Dealing with two shocks at the same time—lingering drought and intense floods—WFP creatively sourced and delivered food to reach almost 750,000 people in February. In places where heavy rains and flooding cut off access to communities, WFP used canoes and river barges to reach people in need. By the end of the month, food prices started to fall as WFP food helped stabilize food markets. Families also started to reap the rewards of their green harvest, a combination of corn seeds and vegetables.

As farmers started to prepare for the main cereal harvest in April and May, WFP started making plans to wind down the emergency operation. The agency went from reaching 511,000 people in April to 245,000 people in June. Though 50,000 people were still recovering from the impacts of the cyclone, Mozambique’s agricultural prognosis seemed good for the first time in almost a year.

At last, the emergency was over.

What Comes Next

By the time I left Mozambique, the aspirations of farmers hoping for a good harvest still rang loud in my head. For the fortunate ones, the lean season would end. For those less fortunate, WFP food assistance would be there for them over the next couple of months.

“Before the harvest, our humanitarian imperative was the greatest,” said Karin Manente, WFP’s country director. “But now after the harvest—in those communities where the harvest will be bad, fail, or be low—we will continue to be engaged. But our focus then will be on resilience.”

Over my time in Mozambique, I saw incredible pockets of resilience. Close to 100,000 students participated in WFP’s emergency school meals programs across 254 primary and 11 secondary schools. More than half of the children who had previously dropped out of primary schools came back to the classroom following the introduction of these programs.

Under a scorching sun, I watched a mother and father wait for their last monthly ration of emergency food assistance on a large green savannah. The road they stood alongside had recently been ravaged by severe drought, then severe flooding. Only a pathway of caked mud remained, connecting the outside world to hundreds of families who relied on each other and WFP to survive the unpredictable.

There were no illusions about the task at hand.

The fear that drought would return was ever present in my conversations; the chance that floods would return was highly likely. The science, after all, suggested that both extreme weather events would happen more frequently.

But for now, the emergency was over. For now, there were so many people who could rest easy knowing they were okay. For now, WFP was receding into the background.

For many farmers, the familiar cycle began again. Since last August, Ivone and her neighbors have watched their seed multiplication project in Magude triple to more than 3.5 acres of land. The community is planting a fourth field in the months ahead, hoping to harness the water from a nearby river with the help of a water pump.

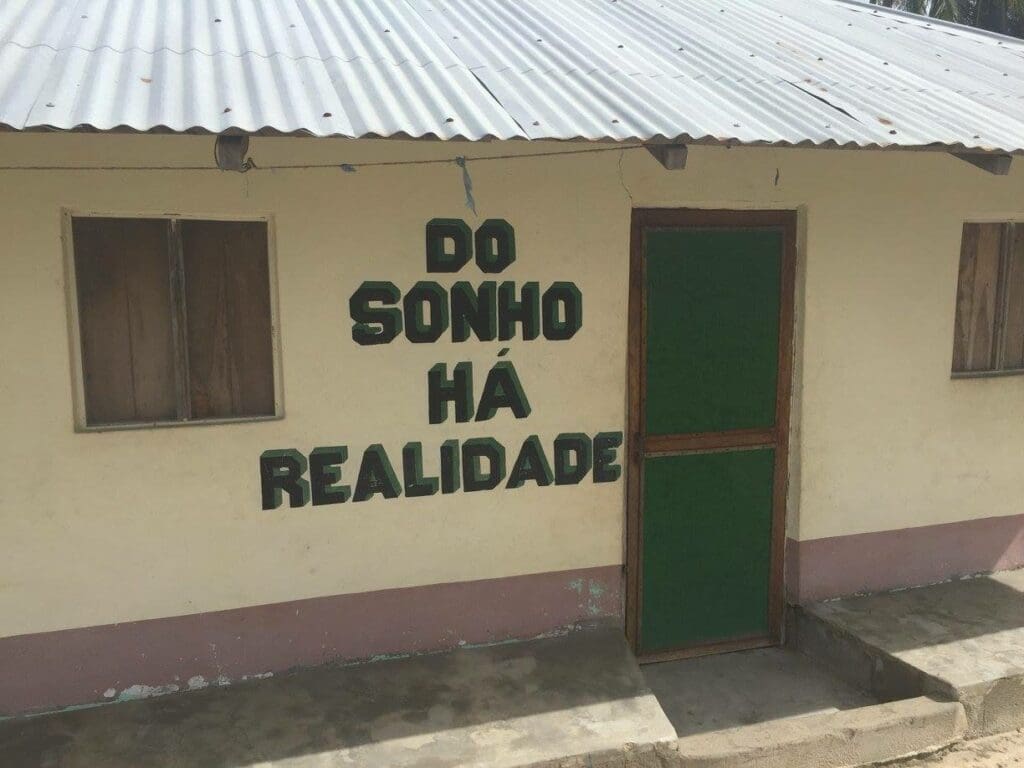

“Our dream is to expand,” Ivone said. “We are going to plant seeds that are drought-resistant with other crops that we can make part of the same sowing in the same field.”

This dream—this future—was born from the grips of hunger. And it all started with an empty plot of land, cassava seedlings, and the promise of food—bags of corn, beans, peas, as well as oil, delivered every month.

This is what dreams were made of.

Life-changing food is ready to be delivered. All that's missing is your support.