How Do You Feed Over 5 Million People a Month?

A Life Interrupted

It’s been more than four years since Nasreen left Syria, but it feels like a lifetime ago. In 2012, she was forced to flee her home in the northwestern coastal province of Latakiya, a mountainous region that shares a border with Turkey and has extensive agricultural holdings. Like many of her neighbors, she and her family held on as long as they could, but the country’s civil war eventually invaded their daily lives and forced them to leave everything behind. They found relative safety roughly 10 miles across the Turkish border.

Nasreen chops parsley to be used in her tabbouleh salad, along side fresh lettuce and green onions she bought with support from WFP.

Nasreen, 21, now lives in Kahramanmaraş camp in southern Turkey with 18,000 other Syrian refugees who, like her, are waiting until it’s safe enough to return home. Though the camp is only a few hours’ drive, without border crossings, from her old home, it feels like a different planet. Situated in the southeastern Anatolia region, the camp was opened in 2012 and sits on an arid plane outside of the nearby city of the same name, lined with row after row of tents.

“In the beginning, they [local authorities] brought us food but we couldn’t eat it — it didn’t taste like our food,” said Nasreen, describing the difficulty she and her husband had adjusting to their new lives as refugees in Turkey. They found themselves in a foreign land, surrounded by unfamiliar food and language, forced to live in a boarding school until formal accommodations were ready.

Meanwhile, back in Syria, a half-built home stood empty. Her family had been building a new house for Nasreen and her then-fiance when the conflict broke out. When she left Latakiya, it was almost finished. “My husband and I used to dream about our house when we were engaged,” she recalls. “In the end, we never got it.”

Nasreen married her husband soon after arriving in the camp, which afforded them their own tent. Soon after, she became a mother and now has a second child on the way. Her entire family depends on the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) to survive.

Eventually, grocery stores were built in the Kahramanmaraş camp, letting refugees shop for Syrian food items that would otherwise be unavailable. Nasreen receives an electronic food cards or “e-card” from WFP, which is loaded every month with credit at local markets.

Nidal left his home in the Syrian city of Idlib in 2011, settling with his family in the Boynuyogun refugee camp in southern Turkey. Here he shops in the camp’s supermarket with a WFP e-card for a wide variety of high quality fruits and vegetables.

Pushed from their life into circumstances far beyond their control, refugees like Nasreen are afforded dignity through WFP’s e-cards, which enable families to select their own groceries instead of lining up.

With access to fresh ingredients, they can now create the culinary dishes that help them stay connected to their homes and heritage. “Now everyone is cooking in their tent whatever they feel like,” said Nasreen, as she prepared tabbouleh, a famous Levantine staple salad made with bulgur, parsley, scallions, lemon juice, mint and olive oil.

How Do You Feed Over 5 Million People a Month?

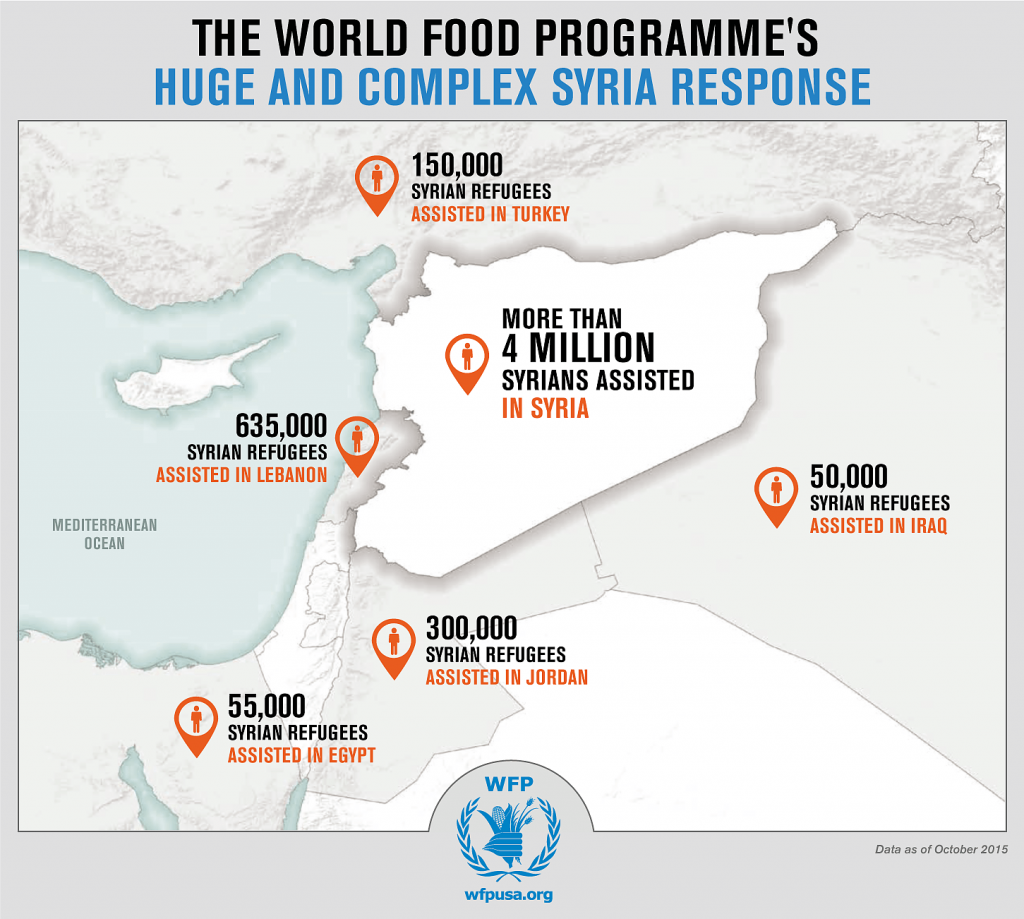

In order to feed beneficiaries like Nasreen, WFP has deployed every tool at its disposal. Since 2011, the agency has responded to the immediate needs of those affected by the Syrian conflict, rapidly scaling up operations as the crisis spread and vulnerabilities increased. Right now, WFP provides monthly life-saving food assistance across most of 14 Syrian governorates, currently serving around 4 million people on a monthly basis. Outside of the country, Nasreen and almost 1.4 million other refugees receive food assistance through e-cards inside and outside refugee camps.

Feeding over 5 million people each month is an immense undertaking and the Syria emergency response has become WFP’s largest and most complex operation to date. Through cross-border convoys, airlifts, freighters and difficult-to-negotiate ground transport, the agency is able to get the food where it needs to go.

A cross-border convoy from Turkey travels through Syria’s Aleppo province. This convoy carried enough food to feed 58,000 people for a month and 10 temporary warehouses to boost storage capacity.

WFP also heads the Logistics Cluster, meaning the agency is responsible for the warehousing and transportation of not just food, but medical and health supplies, shelter, fuel and other items required for humanitarian response across the entire region.

From his office and residence at a fortified hotel in central Damascus, Louis Boshoff spends his days coordinating a multifaceted web of transport activities for the Logistics Cluster. “The scale of the Syria crisis is getting worse every day,” Boshoff told WFP’s Alexandra Murdoch last August. However, “without WFP and other agencies working tirelessly to access those displaced in Syria and the neighboring countries, the humanitarian situation would be much worse.”

Getting Food to Those Who Need It

The problem in Syria, as in the rest of the world, isn’t just that there is not enough food to go around. Instead, it’s access. Every day, WFP staff grapple with how to safely and quickly transport food to those who desperately need it in the midst of a war.

A baker watches over his bread at a WFP-supported bakery in northeastern Syria’s Al Hasakeh governorate.

Through the Logistics Cluster, WFP works with both international and local partners like the Syrian Arab Red Crescent and the International Committee of the Red Cross to get aid into hard-to-reach areas.

“Last year, alongside other agencies,” said Boshoff, “we transported vital food, medicine, water and sanitation products into a town where people have been cut off from their most basic needs since 2012.”

The Bab al Hawa border crossing between southern Turkey and northern Syria is a main conduit for such emergency relief. WFP’s logistics hub in the Turkish city of Rehyanili is only a few miles from the border and serves as a transfer point where rice, wheat, flour and ration boxes from the port of Mersin are unloaded into Syrian trucks contracted by WFP.

Syrian Arab Red Crescent volunteers distribute bags of WFP wheat flour to internally displaced families in Syria.

A strict monitoring process is carried out, including weighing and x-raying the trucks, and inspecting their cleanliness and contents before and after the food is transferred by a United Nations (UN) Monitoring Team, Turkish customs officers, UN-contracted implementing partners, and Syrian laborers. This entire procedure can take up to six hours, finally ending with the trucks making their way across the Syrian border and to their final destination in war-torn towns and villages.

Internally displaced Syrians collect food items from a WFP distribution point in Damascus.

In 2015, WFP delivered food to at least 1 million people in hard-to-reach areas in Al-Hassakeh, Homs, Idlib, Hama and Aleppo through inter-agency cross-border convoys.

Food as a Lifeline

For those outside of Syria like Nasreen, food is sometimes the only lifeline to home. In 2013, WFP introduced e-card technology, shifting from traditional paper vouchers redeemable for food items. With e-cards, beneficiaries are able to access their assistance as soon as it is available.

This new technology has not only saved transportation and storage costs, it has also allowed Syrian refugees to select fresh produce and dairy — items not typically available through traditional food rations, which tend to be grains that don’t spoil as easily. Now, families can shop on their own schedules and create their own meal plans using a wider variety of ingredients.

Food items available to WFP beneficiaries at the supermarket in Harran camp, Şanlıurfa, Turkey.

Food items available to WFP beneficiaries at the supermarket in Harran camp, Şanlıurfa, Turkey.

E-cards benefit host countries as well. When food and groceries are purchased from local markets with WFP’s e-cards, they boost small business owners and markets overall. For instance, WFP estimates that its e-card program in Jordan will create more than 350 jobs, generate roughly $6 million in tax revenue and between $255 million and $308 million in indirect benefits to the country’s economy in 2015.

Nidal from Idlib uses his e-card to pay for groceries at the Boynuyogun refugee camp in southern Turkey.

Other aid agencies are utilizing WFP’s e-card technology too. Last winter, when the Middle East was hit by extreme weather that blanketed refugee camps in snow and plunged temperatures below freezing, WFP and UNICEF launched a winter cash-assistance program so families could buy warm clothing using WFP’s e-cards. This kind of rapid response is exactly why e-cards were launched in the first place. “The vision was for other relief agencies to use this platform to provide their assistance to Syrian refugees,” said Dorte Jessen, until recently WFP’s Deputy Emergency Coordinator in Jordan.

Ongoing Challenges

Syria is still locked in a brutal civil war that has lasted more than half a decade, displaced an estimated 12 million people from their homes and killed over 200,000. In this ongoing nightmare, food is being used as weapon of war through siege.

The United Nations General Assembly Human Rights Council’s Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic described besiegement in Syria as being “conducted in a ruthlessly coordinated and planned manner, aimed at forcing a population, collectively, to surrender or suffer starvation.”

Children cook food in an open area at Al-Riad shelter, Aleppo, Syria, February 2015.

Many in Syria persevered as long as they could, but after six long years of war most believe the end is nowhere in sight, prompting some to risk everything for a chance at a better future overseas.

In this context, WFP’s food assistance is one of the few stabilizing forces in the region. Though the suffering of millions affected by this crisis can only be alleviated through a viable political solution, the humanitarian community is responsible for aiding those in need no matter what.

Until displaced families can return safely to reestablish their lives and livelihoods, it is WFP’s mission to provide them with the food that they need.

A Lifeline on the Frontlines

Back in Kahramanmaraş, Nasreen finishes her tabbouleh. “Everyone makes it the same way. I learned from my mom, but every woman knows this recipe in Syria,” she says with pride.

Nasreen mixing ingredients into her tabbouleh.

Even after four years, she still dreams of the day her family can return to their country and rebuild their life.

“When I go back, I will sell whatever I have and we’ll build our house again with my husband because I want my son and my unborn child to live there.”

WFP’s vital food assistance helps Nasreen’s family — and millions of other Syrians seeking refuge — survive a war that has torn their country apart. For these families, food from WFP represents one of the few remaining sources of hope.