Half-Moons for Full Stomachs

Niger faces no shortage of challenges. Among the poorest countries on the planet, rapid population growth means more mouths to feed and young men and women to employ. Two in every three people in the country are below the age of 30. Environmental degradation threatens its landscape, with the Sahara Desert creeping south by about a mile each year. Meanwhile, 80 percent of Nigeriens survive on subsistence agriculture, a livelihood currently under profound stress.

A farmer sows seeds into a half-moon at Illimazak, Tahoua region, Niger.

Despite the forces that have pushed Niger to the bottom of the Human Development Index, the country has, until recently, remained relatively peaceful. In fact, it has been rightly called “a good place in a bad neighborhood.” Violent extremists have established networks in Burkina Faso, Mali, Nigeria and other surrounding countries. Niger has close to 4,000 miles of porous borders with these countries, and thus, Niger is highly vulnerable to their happenings. The country is at a tipping point, in a region at a tipping point, on a continent at a tipping point, in a world at a tipping point.

Since May of 2019, over 40,000 Nigerian refugees have crossed the Nigerien border into Maradi, seeking safety and distance from Boko Haram. This has placed great stress on already impoverished communities, many struggling to feed themselves or their families. Yet, Niger has long been a connector between worlds and cultures and may hold a potential blueprint for prosperity and stability in the region. Preserving development gains there will be critical.

I traveled to Niger in early October 2019 with a delegation of staff from Capitol Hill to see this nation’s situation for myself and learn more about how U.S. government support is helping organization’s like WFP move the needle on hunger.

The View From Above

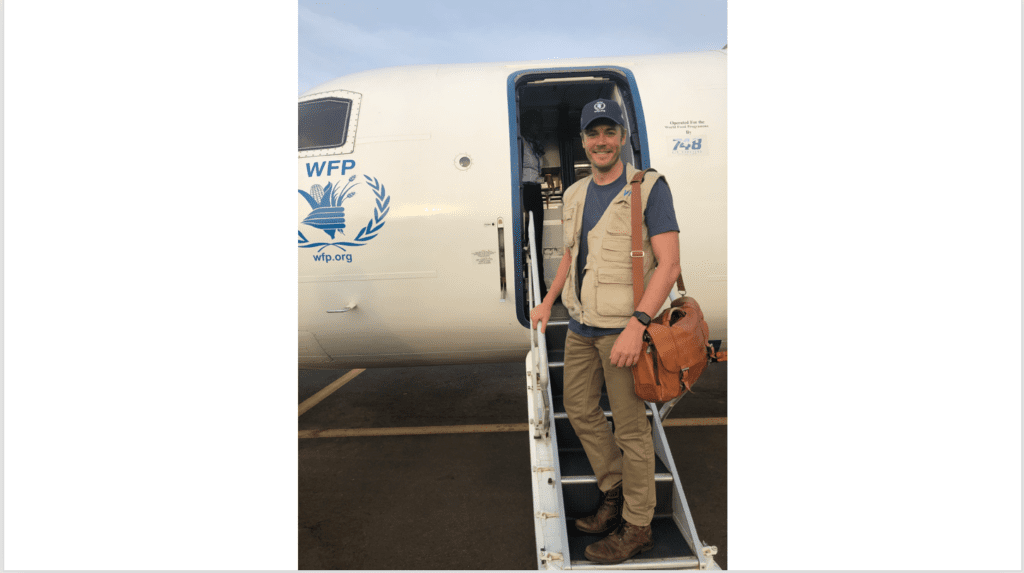

A UNHAS flight.

Soon after arriving in Niger, we take a United Nations Humanitarian Air Service (UNHAS) flight from its capital, Niamey, to the region of Maradi 300 miles to the east. The Air Service is a little-known activity run by WFP that allows the organization to quickly move humanitarian workers from a variety of agencies closer to people in need. It is just one example of WFP’s logistics prowess. Around the world on any given day, WFP has around 5,000 trucks, 92 aircraft, and 20 ships on the move. It is a humanitarian logistics operation of unmatched proportion.

Chase Sova (second from left) and the WFP delegation in front of the UNHAS flight.

There is not a cloud in the sky blocking our view as our UNHAS flight climbs to altitude, yet very little evidence of human life breaks the red-dirt landscape below during our flight. Most of the landmass in this landlocked country is uninhabitable desert or home to the arid conditions of the Sahel, historically home to nomadic communities like the well-known Tuareg pastoralists. Today, desertification and land degradation challenge these traditional ways of life, sometimes forcing herding communities into conflict with sedentary farmers in a fight for land and water.

The Moons Below

On this day, though, it is greener than I’m accustomed to seeing the Sahel. This is both because the rainy season is coming to a close and because of investments made by WFP and partners to transform the landscape. Since 2014, WFP has been engaged in resilience building activities like its Food Assistance for Assets programs. In exchange for food rations or cash transfers, food-insecure people in communities WFP serves participate in projects like building roads and ponds, tree planting and, increasingly, the digging of so-called “half-moons.”

Half-moons in Niger.

The half-moon is a micro water catchment about two meters across at its widest point, a semi-circle carved out of the hard soil. Separated by as little as a few feet (depending on expected rainfall and ground slope), over a larger area the half-moons resemble a field full of flying saucer crash zones – the red dirt mounded up around the area of impact. When they are working well, half-moons don’t look like this at all. Instead they are overflowing with grasses, crops like Sorghum and Millet and even fruit trees. It’s only when they are being constructed that you can see their shape – and their genius.

Half moons in the Maradi region of Niger.

A Force for Change

As our caravan pulls up to the community of Boussarague, evidence of half-moons is all around. Among the first communities to participate in this kind of project, Boussarague has transformed. Over 400 households have rehabilitated almost 3,000 acres of land, mainly for use in producing food for livestock. The abundance of grasses and leaves produced in the half-moons has, at the same time, increased the number of livestock in the area and led to reduced conflict between herders and farmers. Productivity has risen so much that the community has established a shared cereal bank, with a portion of the grain headed directly to local school meals programs.

A farmer who participates in WFP’s Food for Assets program in Niger shows off his flourishing corn field.

It is through these interconnected results that the impact of a simple solution like a half moon is magnified. Here, half-moons mean reduced conflict over resources like land water, increased attendance rates and performance among young girls at school, reductions in seasonal migration and increased community capacity of the type that might lead to a centralized cereal bank and other community-based social protections. What starts as a hole in the ground can become a force for transformational change.

I’ve heard of half-moons for some time now. To most, the words conjure up images of a smiling moon or even a wheel of cheese. In the world of global food security, though, these half-moons are becoming synonymous with solving hunger and reviving land. I’ve been working in the international development space for my entire career. During that time, I’ve learned to be skeptical of magic bullet solutions to the complex challenge of pervasive poverty and human development. It’s never that easy. I have remarked that, “no quantity of half-moons could ever deliver the Sahel from convergence of challenges that it faces.” Now, seeing the solution firsthand, I’m not so sure that they can’t.

Tipping the Balance Toward Peace

WFP is planning scale up this “integrated package of resilience” to 2 million people across the African Sahel within the next five years. The miracle in Maradi is already happening. But it needs nourishing to scale and truly tip the balances in the favor of peace and prosperity. In many ways, Niger is a poster child for a changing landscape. Humanitarian crises are becoming more protracted, requiring sustained, multi-year interventions and greater coordination with other elements of the U.S. foreign policy toolkit, including diplomatic and security actors.

A female farmer in Niger shows off her harvest.

Broader, unsettling trends in global forced displacement are clearly on display in the country, combined with quickly changing demographics and severe climate impacts. These new demands are forcing WFP and other humanitarian and development organizations to change the way they do business. The question remains whether Niger, with help like this from U.S., UN and other partners, can represent an enduring model for how to successfully overcome this new suite of challenges.

That we succeed in this mission is of profound importance to the people of Niger, to the Sahel, to Africa and to the world.