Why Do Floods Follow Droughts? Look to the Somali Region of Ethiopia.

In the spring of 2019, heavy rainfall and flash floods washed away livestock, homes and public buildings in the Somali Region of Ethiopia, affecting over 165,000 people along the Shabelle river. Ironically, flooding is common in areas that are prone to drought. When the ground is too dry, it can’t absorb rain fast enough so the water runs over land, flooding the surrounding area. Today, the Somali region remains the epicenter of drought and prone to flash floods.

As global temperatures continue to rise, millions of people who are already teetering on the edges of climate-sensitive regions will be pushed further into hunger. Agan Hassan is one of them.

Learn about how climate change it worsening the hunger crisis.

Like many people in Ranranle village that morning, Agan Soyan Hassan was sleeping when the River Shabelle burst its banks and flood water engulfed her home.

She awoke to the shouts of neighbors fleeing the village and to see water soaking the mats on her floor.

Heavy flooding destroyed two main bridges, posing major access problems for the U.N. World Food Programme and other agencies. Here, one of the bridges was washed away entirely.

She rounded up her six children — the youngest of whom is three — and with the help of two neighbors spent the next four hours wading through water to reach higher ground.

She finally found refuge, but the lack of trees meant there was no shelter from the rain. After the waters receded, there was little space left to set up a temporary home.

Three weeks after the floods, a makeshift settlement appeared. Families were sheltering under flimsy structures made of sticks and ragged clothes, with the better ones covered in plastic sheeting.

Agan and her children sat by their temporary shelter. Nearby, pounded corn supplied by the U.N. World Food Programme was spread out and drying on a cloth. Soon it would be hand-ground and cooked into a pancake, known locally as Soor.

Agan explained how her tukul – a cone-shaped mud hut – had collapsed, and how her cow, eight goats and ten hens had been drowned. She was left with six cows and two hens, whom neighbors had helped move to higher ground. Agan’s food supplies were all lost, and her children missed out on school.

Agan and her children relied on the kindness of relatives and neighbors for food, a plastic sheet for shelter, and a few items such as a cooking pot, a kettle and two glasses for tea.

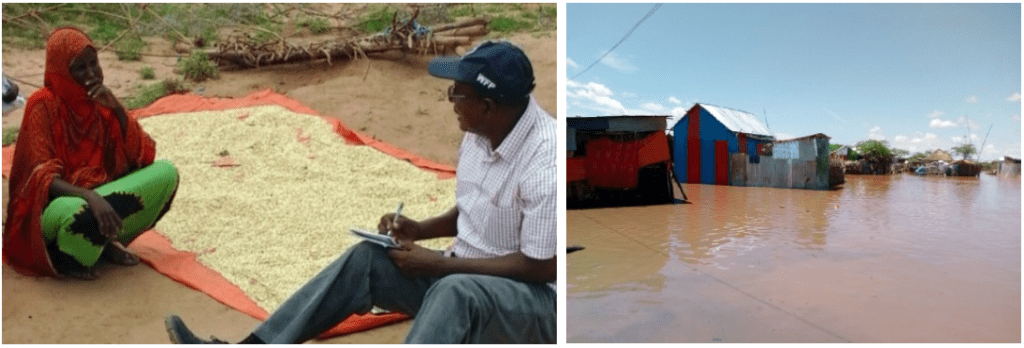

Field Monitoring Assistant Ahmed Ibrahim speaks with Agan Soyan Hassan at a makeshift camp for people displaced by the floods. Many villages and towns like Dolo Odo (pictured right) were left submerged by the rains.

Even before the flood, Agan had been receiving food from the U.N. World Food Programme each month because of recurrent drought in the region. As soon as the U.N. World Food Programme gained access to her neighborhood, she again began to receive food including grains, beans and vegetable oil.

“U.N. World Food Programme food assistance is a glimmer of hope,” said Agan. “When first I saw U.N. World Food Programme trucks arriving, there was a sigh of relief — I was very happy. I knew that my main need would at least be covered, and I started thinking of shelter and my other basic needs.”

It had taken two weeks for the food to get through, as many roads were flooded or even collapsed. Some U.N. World Food Programme trucks became stuck, and reaching communities remained a major challenge. Despite this, the U.N. World Food Programme reached over 56,000 people by mid-April, working with partners including the Government of Ethiopia, UNICEF, the World Health Organization and local NGOs to do road assessments and identify alternative routes where possible. This kind of partnership approach and pooling of skills, resources and local knowledge is vital when faced with such challenging conditions.

Learn about how the U.N.’s different humanitarian agencies work together.

The U.N. World Food Programme will keep working every day to overcome obstacles and reach those in need, so that more people like Agan and their families won’t go hungry.

Right now, more than 80% of the world’s hungry people live in disaster-prone countries. They are struggling harder and harder to withstand more frequent and extreme weather events. To learn more, visit our Climate Change & Hunger hub.

This piece was originally written by Paul Anthem and Ahmed Ibrahim and appeared on WFP Insights.