A Flood of Insights

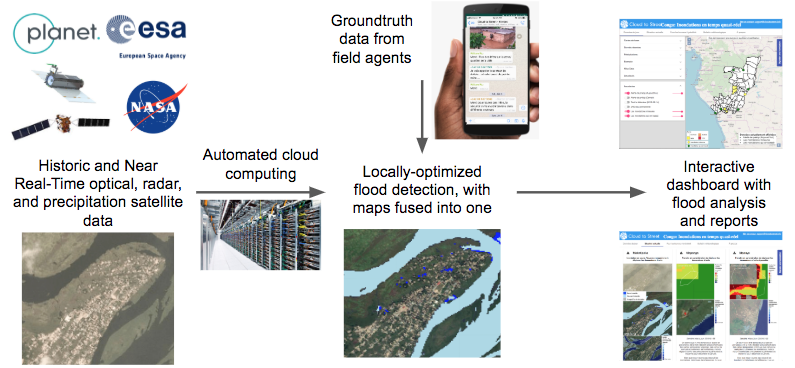

Each year, flooding affects thousands of people in Congo, a Central African nation of four million people. In order to boost national flood response efforts, the government, the World Food Programme (WFP) and Cloud to Street — a data startup — recently piloted an analytics-heavy flood monitoring system. WFP’s Innovation Accelerator provided the funding.

Now that the pilot is over, it’s time to reflect on the experience. Did high frequency satellite imagery analysis help better inform responses to flood events in Congo? What have we learned after six months ?

Flood analytics, in the palm of your hand

About a dozen Congolese government agencies — led by the Ministry of Social Affairs but also including the Ministry of the Interior, the fire service, the weather and hydrology service and many others — got access to a custom-made, interactive online dashboard that Cloud to Street populated with the latest, near real-time maps and analytics.

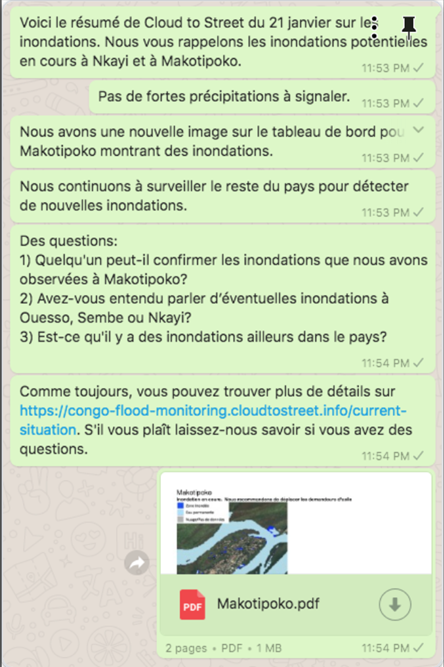

Users were trained and certified at the start of the pilot. They received updates on their phones through a dedicated WhatsApp group that became increasingly active as the pilot proceeded. The data that came in was verified with local field agents who participated in the WhatsApp group.

Results are difficult to pinpoint because, unlike in 2017, there was no major flooding in Congo during the main 2018 rainy season. However, we feel that some of the minor flood events that did occur show that the system we put in place would have helped us detect and react to flooding more quickly than ever before. For example, in the river town of Mossaka, Cloud to Street was able to pick up on flooding that the local media reported on several weeks after.

In the words of the chief of staff at the Ministry of Social Affairs, “Cloud to Street would have helped us to react to major flood situations, like the one in Impfondo in 2017, in a matter of days instead of weeks.”

Unfortunately, the system was not able to pick up on the instances of flash flooding in large towns in the south of Congo in December. This was due to technical issues including cloud cover over the sites, and to the fact that by the time we requested satellite imagery, it was too late to capture the floods. However, the time and extent of the flooding in these cases was well documented on social media and the press, so there wasn’t a pressing need for an active flood monitoring system to trigger action in these areas.

An unexpected achievement: decision support during an influx of asylum seekers

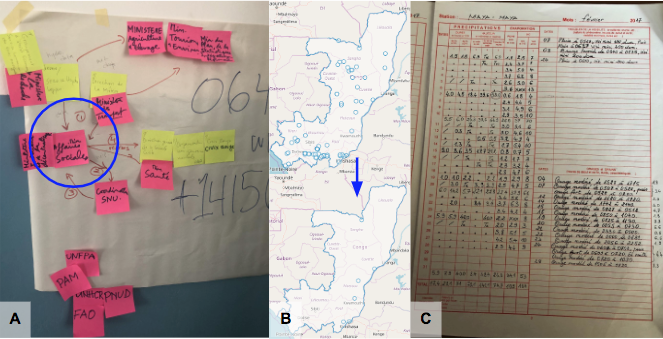

The pilot helped us in one unexpected way. In December 2018, some 16,000 people crossed over from the Democratic Republic of Congo and settled on low lying islands on the Congo river. Initial field visits showed people had settled on a waterlogged island and there was a significant risk of flooding. We asked Cloud to Street for a flood analysis and, in a matter of days, we were able to obtain an assessment of the flood risk faced by thousands of highly vulnerable newly-arrived asylum seekers.

This analysis helped the United Nations’ Refugee Agency, UNHCR, successfully advocate with the government to find safer sites for up to 7,000 asylum seekers that had settled in flood-prone areas. The analysis also had impacts on WFP’s own decision making, including where to set up our temporary food storage infrastructure.

Flood risk assessment enhanced the assistance provided to asylum seekers in December.

What we learned

As other data projects have shown, acquiring data and building the platform is the easy part. Turning the data into information and decisions was the main challenge we experienced.

That’s why we’re proud of the more practical processes we carried out in dimly lit and poorly air-conditioned rooms with post-its and markers in hand. One of these was mapping out the complex decision-making process within the government at the start, which helped us better capture the web of relationships and accountabilities that our data would feed through.

Also, it emerged that having a mobile-friendly dissemination strategy was important to engage with our users and improve coordination. Some ministries have limited access to internet, but most civil servants have data connections and WhatsApp on their phone and could receive flood updates on their personal devices. Connecting with people through WhatsApp was a great way to boost the use of the dashboard. As people received notifications when something new appeared, we noticed an increase in visits to the dashboard.

Being on the same page, or screen

The WhatsApp group allowed users to receive and act on the same pieces of flood information. This is important in a context when government agencies are receiving many pieces of flood information and mostly via word-of-mouth. During floods, conversations actors started notifying each other via the WhatsApps group as they tried to confirm the location and magnitude of a flood event. With all of them on the same page, decision-making would likely be improved.

Where Cloud to Street’s model was not that useful was the urban flooding that took place in December/January. Our approach may need to be tweaked to cover those cases. The system also needs to be tested over a longer period, as the short sprint did not allow us to test all of our hypotheses. More time would also be needed to make people aware of the systems’ potential, especially at more senior levels.

A final point was that we were being watched by people outside Congo. The pilot raised interest in a half a dozen other WFP country offices and prompted a more general brainstorming around how the organization approaches flood mapping at the global level.

But will they buy it?

The replicability of the project hinges on finding the right pricing model. A pilot funded by generous foreigners was welcome, but asking stakeholders to cover costs over the long-term is another matter. The Congolese Ministry of Social Affairs was extremely interested, but considering Congo’s current economic challenges the service is just too expensive for them at the present time.

This raises the question of the viability of the ‘business models’ for flood mapping. Our experience from the pilot has identified three approaches we will further explore. First of all, could Congolese local remote sensing experts offer such analysis at a lower price? Secondly, it could be more scalable and affordable to establish a regional or global service where costs could be shared between a larger number of clients. Finally, we will look into whether existing weather insurance mechanisms could help fund flood monitoring.