The Price Tag of a Poor Diet Is a Lot Higher Than You Think

Can you put a price on the cost of poor diets? The United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) has, and it’s a hefty bill.

Obesity, from eating too much of the wrong foods, and undernutrition, from not getting enough of the right ones, are two sides of the same coin. More and more, these two seemingly separate forms of malnutrition are being seen side by side in the same countries, communities and even families. It’s known as the ‘double burden of malnutrition,’ and countries are paying a heavy economic toll. Children, sadly, are the most impacted.

Billions Lost Because of Malnutrition

While Latin America and the Caribbean have made significant progress in reducing undernutrition over the past 20 years, these regions have simultaneously seen an increase in overweight and obesity, aka over-nutrition. (Click here for a quick explanation of terms.)

A study conducted by the UN World Food Programme in 2017 put a price tag on the burden, showing how Latin American countries are paying for malnutrition directly through healthcare and schooling and indirectly through lost productivity.

We analyzed data from Chile, Ecuador and Mexico and estimated the impact that malnutrition had on net loss of gross domestic product. The results were shocking:

- $4.3 billion a year in Ecuador (4.3 percent of GDP)

- $28.8 billion in Mexico (2.3 percent of GDP)

- $500 million in Chile (0.2 percent of GDP), where undernutrition had already been largely eradicated

Beyond the figures, we found that children are often the hardest hit by this double burden. Here are the main reasons why:

1. Undernutrition impacts the education system

Not getting enough of the right foods affects a child’s education in two ways. Children who don’t get adequate nutrition in the first thousand days from conception to their second birthday have poorer cognitive development. Then, when they reach school age, not having enough to eat during the day means they have trouble concentrating in class. Undernourished children are therefore more likely to have to repeat school years, at a heavy cost to governments and families.

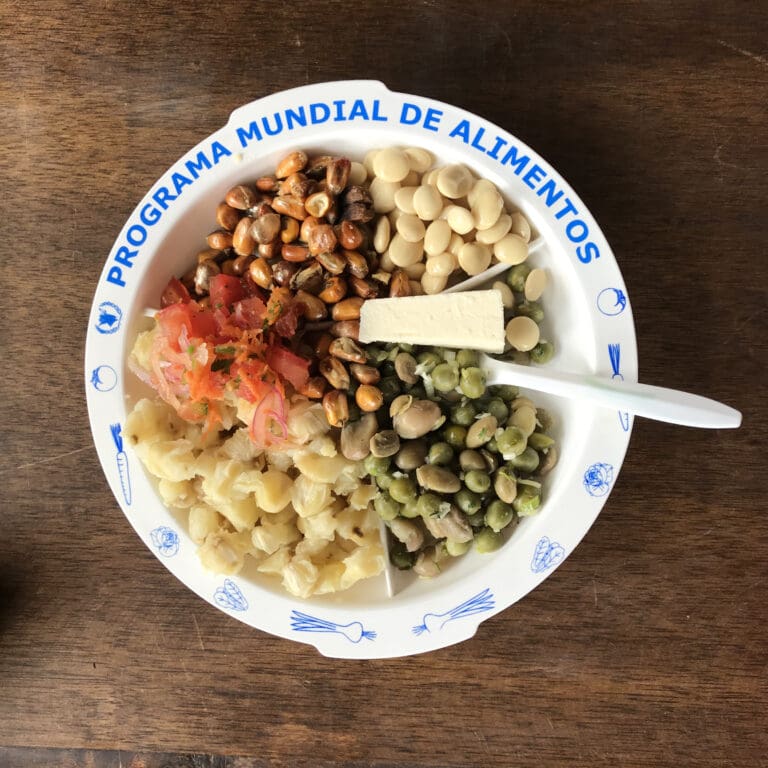

A group of children in Ecuador enjoy a meal as part of WFP’s school meals program.

2. Unfulfilled education potential leads to lost productivity

Children who suffer from undernutrition are more likely to have poorer cognitive development and lower educational levels than well-nourished ones, limiting their work potential throughout life. When they become part of the working-age population, their contribution is often inhibited as a result.

Little Dilan is one year old and lives with his parents in Honduras, the heart of the Dry Corridor.

3. Premature death means lost productivity

The consequences of malnutrition in early childhood can last for a lifetime, and the health implications can be deadly. Premature death from malnutrition means that people either stop being part of, or never become part of, the working-age population. Lost productivity due to early death as a result of undernutrition was found to create a significant burden on countries’ economies.

Jameli Orbelina Casco Gomez sits with her three children outside a nutrition center in Honduras. Jameli receives food assistance from the U.N. World Food Programme and takes her infants Liam and Alexa to the center to be tested monthly for malnutrition.

4. Missed work leads to lost productivity

For children who survive, chronic illness related to overnutrition can lead to missed days of work for medical visits, prescribed rest or sick days. Studies on work absenteeism have found that overweight and obese workers are absent from work more days per year due to illness, regardless of occupation type.

A school meal is made from locally-grown produce and teaches kids about the importance of a health diet.

5. Malnutrition has direct healthcare costs

Both undernutrition and over-nutrition have associated healthcare costs. Children suffering from undernutrition have increased chances of getting sick, particularly with diarrhea and respiratory infections. Over-nutrition can lead to non-communicable diseases such as type II diabetes, hypertension and cancer. Although the health effects may be slow to develop, they are long-lasting and can require years of medical attention.

A mother in El Salvador pays for her shopping at a local grocery store with money she received through the U.N. World Food Programme’s Resilience and Climate Change Program.

According to the study, although undernutrition is declining, over-nutrition is expected to become the largest social and economic burden in the region. That’s why the U.N. World Food Programme is doing everything it can to make sure young kids get the right food at the right time. But we can’t do it alone. We need help from governments, the food industry and individuals like you.

Learn more about the work we’re doing to save children from hunger here, and make your most generous gift today.

The study was carried out by the U.N. World Food Programme and the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), drawing on a methodology originally designed to measure the cost of child undernutrition and updating it to include the impact of overweight and obesity. See the full report here.

An earlier version of this article was written by Simone Gia in 2017 and posted on WFP’s Insight.