TEDx Talks: Are We Ready to End World Hunger?

This spring at TEDx OakLawn, I shared a brief history of the fight against global hunger – and how we’re closer to winning it than ever before.

Albert Einstein’s brain was dissected in 1955, but the world wouldn’t find out for another 20 years. When the news broke that a scientist had been secretly studying Einstein’s grey matter, universities and museums the world around fought to get a piece of the action—quite literally.

But amid the rancor and debate, renowned paleontologist Steven J. Gould quietly recorded this profound thought: “I am, somehow, less interested in the weight and convolutions of Einstein’s brain than in the near certainty that people of equal talent have lived and died in cotton fields and sweatshops.”

Watch The Full Video:

I think about this almost daily in my job at the World Food Program USA, because an even greater number have died of hunger. We see it in the news everyday—a rise in the absolute number of hungry people, an unprecedented four looming famines and of more hungry people displaced from their homes because of violence, conflict and persecution than any other time since the Second World War.

But it’s worth recalling a quote from the author, F. Scott Fitzgerald: “The test of true intelligence,” he wrote, “is the ability to hold two contradictory thoughts at the same time.” This is fundamentally true of global hunger today. Because over the last 20 years, over 200 million people have been lifted out of hunger. Famines still occur, but they kill far fewer people than ever before thanks to early warning systems and improved humanitarian responses. We have never had better tools to fight food insecurity.

At the risk of quoting another 20th century author, in the fight to end hunger, it is the best of times and it is the worst of times. So while the headlines can feel disheartening, as a person that follows global hunger trends for a living, I can tell you this with absolute certainty: We are winning the long game in the fight to end hunger.

The “Availability Heuristic”

Consider these two headlines:

- World Faces ‘Unprecedented’ Hunger as Famine Threatens Four Countries

- World Hunger is Increasing Thanks to Wars and Climate Change

Stories like this come at us at warp speed today—a never-ending stream of push notifications onto cell phones that never leave our hands.

The frequency with which we see information like this is important for how we perceive the world. In his latest book, Enlightenment Now, famed psychologist, Steven Pinker describes a phenomenon called the “availability heuristic.” This is the idea that people estimate the probability of an event by the ease with which instances come to mind. With hunger, the instances are many. If we were to allow the headlines of the day to dictate our assessment of the state of food security in the world, we’d be overwhelmed by our apparent failure. Because this is what global hunger looks like over the past three years (Figure 1).

Between 2015 and 2016, the number of hungry people on the planet rose from 777 million to 815 million, driven by a proliferation of man-made crises. Increases in the outright number of hungry people in the world have happened in the past, as recently as a decade ago following the global food price spike crises of 2007/8. While there are important (and worrying) reasons to believe that this upward tick may be unique relative to previous “relapses,” in the words of Steven Pinker: “It would be astonishing if any measure of human behavior with all its vicissitudes ticked downward by a constant amount per unit of time, decade after decade and century after century.” He states further, “Seeing how journalistic habits and cognitive biases bring out the worst in each other, how do we soundly appraise the state of the world? The answer is to count.”

More specifically, we count further back in time. While it is true that the number of hungry people is on the rise again, the general trend in hunger over the past decade tells a far different story (Figure 2). It wasn’t long ago, in fact, that we were speaking of a billion hungry people on the planet. This recent spikes hides a brighter medium and long-term trend.

As we broaden our lens even further, there is more good news. Thanks to research by Alex de Waal, we’re able to see dramatic progress in with regard to famine prevention and response specifically (Figure 3). In his latest book Mass Starvation: The History and Future of Famine, de Waal shows that deaths from famine today are occurring at a fraction of what they have historically. “Our ultimate goal,” writes de Waal, “is to render mass starvation so morally toxic, that it is universally publicly vilified. We aim to make mass starvation unthinkable, such that political and military leaders in a position to inflict it or fail to prevent it, will unhesitatingly ensure that it does not occur, and the public will demand this of them.” There is some evidence to suggest that we’re doing just that.

In short, we can fight the availability heuristic when we choose to take a step back. It is when we look at progress in the long arc of human history that we see just how close we are to ending hunger for good. Hunger is not just a challenge of our generation—it is a battle that human beings have been fighting for millennia. And the story of our progress in ending hunger falls into clear stages, or quarters if you’ll allow a football reference. This is how that game has played out.

The First Quarter

In the first quarter, we fought a battle against population growth. Thomas Malthus, the English philosopher and cleric, prophesized in the 1798 in his book, Essay on the Principle of Population, that food production would not keep pace with population growth, leading to resource competition, violent conflict and mass starvation. It was through war and suffering that equilibrium would be returned to the global food system.

Thus began the battle between “Malthusians,” like Thomas, and so-called “Cornucopians”—those that thought humans would successfully engineer their way out the population dilemma. The Green Revolution in the 1960s and 70s successfully staved off Malthus’ doomsday scenario on a global scale, with industrial agriculture and improved seeds and practices winning the day.

When Malthus wrote his famous essay, the Earth was home to about a billion people. Today, we number over seven billion—and we produce over 2,500 calories for every man, woman and child on the planet. And while we will need to increase production by 50 to 70 percent to meet a population approaching 10 billion by 2050, this is well within our reach.

Thomas Malthus’s doomsday population bomb theory—carried forward by modern theorists like Paul Ehrlich—has been called a “zombie concept” by experts like Alex de Waal, because it is one that “scholars of agricultural economics have continually refuted, but it still keeps coming back to life to torment the living.” Generations after Malthus, the idea that population growth will outstrip food production has been thoroughly debunked.

The Second Quarter

In the second quarter, the central challenge in feeding the world was a natural extension of the first. If we accept that we can feed a growing human population, the next logical question is whether we can do it sustainably. Years of industrial agriculture and monoculture production wreaked havoc on our environment. After all, the same technology that fueled our bombs in the Second World War had been put to work in our fields. It can take 1,000 years to develop an inch of topsoil through natural processes, and we did away with a lot of it in just decades.

These are fragile systems, and we know more about the surface of the moon than the three feet of soil beneath us. David Attenborough once said, “If you believe you can have infinite growth on a finite planet, then you are either a madman or an economist.” I might add 20th Century farmers to this list.

But it was in this quarter that we started to appreciate ecological tipping points and began to talk about things like “planetary boundaries.” We learned that our agricultural practices were contributing to 25 percent of all global greenhouse gas emissions, making climate change worse. As a general rule-of-thumb, climate scientists expect a 10 percent drop in crop yields for every one degree Celsius rise in mean global temperatures. We’re on pace for three degree increase by the close of the century. As many as 200 million people will be pushed into poverty and hunger by climate change if left unchecked.

Carryover Cornucopians from the first quarter clashed with ecologists like William Vogt in the second. Environmentalists sounded the alarm bells, arguing for the complete transformation of our food systems toward more sustainable models. Charles C. Mann refers to these two schools of thought as “wizards” and “prophets”— Wizards engineering their way out of this new ecological problem following the Cornucopian playbook and prophets faithfully stewarding the planet’s limited resources.

As a result, and in a hand-in-hand walk between Wizards and Prophets (sometimes begrudgingly so), we’ve already started to roll out common sense strategies like cover cropping and zero till agriculture. We developed new plant varieties using genetic engineering—not for commercial pesticide resistance like you so often read in the news, but to deal with things saltwater intrusion from sea level rise and drought from changing rainfall patterns. We’ve meticulously cataloged seeds and we’ve seen dramatic growth and interest in local food production. Hypotheses like “can organic agriculture feed the world” have been thoroughly tested, and the results are promising.

The Third Quarter

In the third quarter, we acknowledged the link between agriculture and nutrition. As strange as it may sound, we long considered agriculture and nutrition as two distinct concepts. Thanks to research on child and maternal health, we know that children who do not receive proper nutrition in their first thousand days of life will experience a lifetime of negative affects —physical stunting, reduced educational achievement and economic performance. These impacts costs economies trillions of dollars each year.

Meanwhile, in the industrialized world—and increasingly in developing countries—societies face the dual burden of hunger alongside obesity. At least as many people are obese on this planet as are hungry, well over a billion people. Josette Sheeran, former Executive Director of the World Food Programme, referred to our improved understanding of nutrition as the latest “burden of knowledge” facing hunger fighters.

We’ve translated this burden into specialized food aid products like “Plumpy’Nut” that can bring a child back from the brink of starvation. We’ve bio-fortified staple crops with Vitamin A and Zinc and other vitamins and minerals—so effectively that the minds behind this were awarded the World Food Prize in 2016. We’ve renewed efforts to get mothers breastfeeding around the world. This is how we’re closing out the third quarter. We’ve moved from trying to feed the world to trying to nourish the world. The next big idea that changes the course of humanity—the next Einstein-sized idea—may come from a truly unsuspecting place, but it will not come from the mind of a child who is stunted.

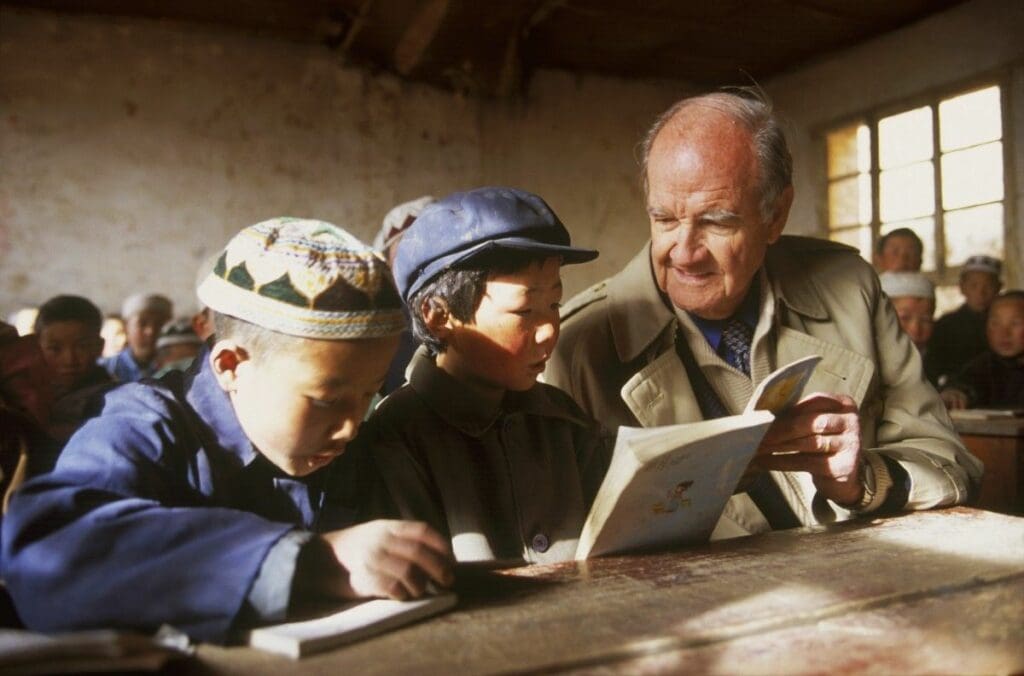

Across these quarters, it is not by the immutable laws of physics that hunger has declined—quite the opposite. It has been through the unlikely march of human progress in the face of overwhelming odds. Hunger hasn’t declined naturally, someone had to act. It was our early ancestors domesticating wheat in the Fertile Crescent 10,000 years ago; it was Norman Borlaug developing dwarf wheat in a laboratory in Mexico that would spark the Green Revolution; it was Senator George McGovern shepherding the idea of a World Food Programme into reality.

*George McGovern reads with students in a rural Chinese primary school.

*George McGovern reads with students in a rural Chinese primary school.

In the long struggle between humans and their natural environment, humans have been putting their thumb on the scale in ways big and small, tipping the balance in our favor—“Wizards” and “Prophets,” “Malthusians” and “Cornucopians” alike.

So let me say this again: We are winning the long game in the fight to end hunger. We asked ourselves, “Can we end hunger in the face of population growth?” We answered a resounding yes. We asked ourselves, “Can we end hunger sustainably in the face of population growth?” We wrote a playbook and we’re rolling it out. We asked ourselves, “Can we end hunger sustainably and nutritiously in the face of population growth?” That’s the mission that we’re currently on.

Human beings have built a doomsday bunker for plant genetic material in the frozen arctic of Norway. We are leveraging the big-data revolution to guide our tractors with satellite precision. WFP has adopted block-chain technology—the foundation of bitcoin and cryptocurrencies—to deliver humanitarian assistance and improve the efficiency of their supply chains. Meanwhile, in blue skies research, scientists are developing plant varieties that photosynthesize more efficiently and non-leguminous crops that fix nitrogen in the soil. We are questioning the way we do things. We are even questioning whether food needs soil—there has been a dramatic increase in hydroponics and vertical gardening. We have thrown everything we have at the problem of hunger—and it’s finally sticking, at scale.

This is good news story, to be sure, but this narrative is not meant to lull us into apathy. Bending the hunger curve toward zero has long relied on the extreme urgency of now. Trends only emerge as time piles up, and positive trends like the one we’ve experienced in global hunger only happen when we take concerted and sustained action. We cannot afford to take our eye off the ball, because we’re entering into the fourth quarter.

The Fourth Quarter

Many a game has been lost in the fourth quarter. In this quarter, the long trajectory of progress in the fight to end hunger meets head-on with a rise in global conflict. We’ve seen an increase in state fragility in the world. Over 60 percent of the world’s hungry live in conflict-affected countries. Almost 122 million, or 75 percent, of stunted children under age five live in these same places. Man-made conflict drives 80 percent of humanitarian spending while natural disaster accounts for just one in every five dollars—a complete reversal from 20 years earlier.

But here is what is important. This collision between hunger and conflict forces us to acknowledge the root political causes of hunger—something we have long ignored or at least under-appreciated. Hunger has always been a technical problem—“How do we grow more, better?” But we’ve done away with those technical barriers in the first three quarters. The only remaining hurdle to ending hunger for all time is abundantly political.

Once we accept that food security is fundamental to peace and security, we are forced to do something about it. It’s not just a matter of doing more than the next donor on moral or economic grounds or making investments in agricultural to tick a box. In the fourth quarter, food security will be seen as a pillar of global stability. And it needs to be, because that’s how we finally get the job done.

George McGovern, a former U.S. Senator and prominent anti-hunger advocate, wrote in his 2000 book, The Third Freedom: Ending Hunger in our Time, “I give you my word that anyone who looks honestly at world hunger and measures the cost of ending it for all time will conclude that this is a bargain well worth seizing.”

We are the Zero Hunger Generation—the first generation in human history capable of seizing that bargain. Pause for a moment and think about what that means in practice. Human beings have been on this Earth for around 150,000 years. For the first 149,950, the baseline condition for humanity has been poverty, hunger and desperation. Yet here you are, reading this in 2018 (or beyond) with all of the tools to finally watch hunger stop.

In the long arc of human history, the world has never been more full of promise.

Watch The Full Video

*Chase Sova is the senior director of public policy at WFP USA.