Just below the Sahara desert sits a vast strip of land that stretches across the entire African continent, where the stakes for rain and peace are high. It’s called the Sahel, and in the center of it are Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger. These three countries are facing a toxic mix of escalating armed conflict, displacement, hunger and widespread poverty – all compounded by the severe impacts of climate change and COVID-19.

The Environment: An Unpublicized Victim of War

In the Sahel, seasonal rains only come once a year to small plots of farmland that provide food to millions of people. Farmers depend on this brief rain to grow good harvests to feed their families, and those who raise livestock rely on it to replenish grazing land for their animals.

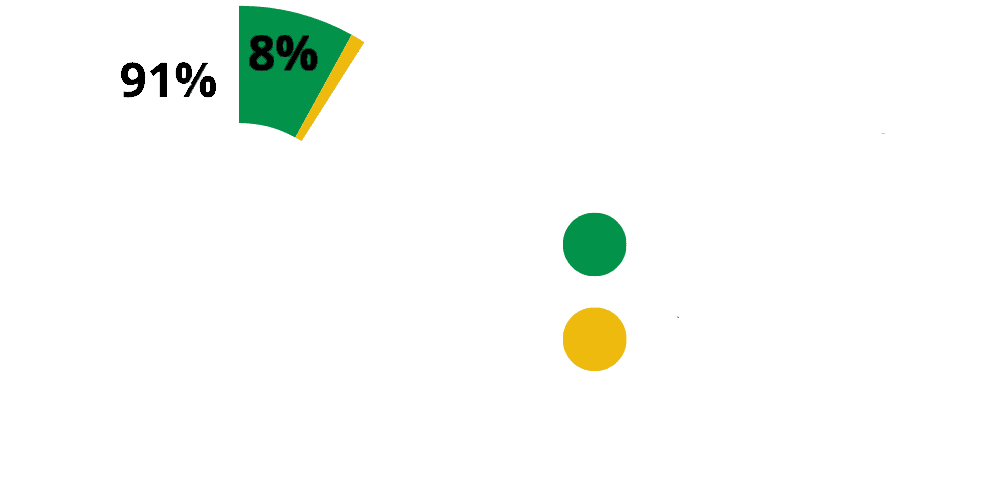

For the past few years, erratic rainfall in the Sahel has contributed to a smaller annual harvest, threatening livelihoods and leading to an early hunger season — the time of year, every year, when food runs out. While higher rainfall is predicted to fall this year, it may not be enough to ease the suffering of millions. By the time the hunger season hits in June, 5.4 million people could not know where their next meal is coming from.

Where Violence and the Environment Meet

Violent clashes between armed groups and civilians have killed scores of people, forced hundreds of thousands to flee their homes and pushed whole communities to the brink of starvation. Violence has continued to escalate in the northern and central regions of Mali, forcing over 300,000 people to flee their homes in search of safety. In Burkina Faso, 1.1 million people are internally displaced – the majority of whom are small-scale farmers who have had to abandon their fields and are no longer able to grow crops. For the third year in a row, conflict in Burkina Faso could deter agricultural productivity and humanitarian assistance.

In the Sahel, the risk persists of conflict spilling over into neighboring countries around the Gulf Guinea including Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Benin and Togo. The region is a tinderbox with the capability of triggering a humanitarian crisis across West Africa.

“This is definitely a risk we should be concerned about,” says Areva Paronjana, a Regional Security Information Analyst for the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) in West Africa.WFP/Marwa Awad

Millions Will Need Emergency Food Assistance

The arid belt of the Sahel stretches from Senegal on the coast of West Africa to Djibouti on the east. Hundreds of millions of people call the region home, but for years, this area has suffered the effects of frequent drought, desertification and other symptoms of a changing climate. In recent years, armed groups like Boko Haram have exacerbated the situation, displacing people from their land.

When harvests are low and livestock are unable to survive, people often resort to short-term coping strategies with perilous long-term effects. Many sell off assets like tools and animals. They eat fewer meals or consume inexpensive, poorer-quality food. Some migrate in search of jobs or food, while others consider joining terrorist groups that offer a monthly stipend or protection, taking advantage of people’s desperation.

While the “hunger season” has been a reality for families in the region for a long time, increasing conflict and insecurity has made the situation more complex.

In northern Mali, N’fa Adama Traore and his community had been living off the land near the Niger River for nearly 40 years. But land disputes with neighboring communities in 2019, as well as violent attacks by armed men nearby, forced his community to flee from their homes.

The Lake Chad area of the Sahel has seen its primary water source shrink by nearly 90 percent in the past 50 years, and armed conflict has become prevalent, strangling trade flows and triggering displacement.

What Will It Take to Save Them?

The rise in conflict is devastating agriculture and rural economies. The U.N. World Food Programme is doing everything it can to provide food assistance to crisis-affected communities through food vouchers, cash transfers or direct distribution of rations while simultaneously providing school meals, nutritional support to women and children and investing in small-scale farmers.

It’s difficult, dangerous work. The rise in armed fighting is limiting the U.N. World Food Programme’s access to families in need and making it harder for humanitarian agencies to carry out their life-saving work. Meanwhile, millions of lives are on the line and the international response has been relatively quiet. Why?

“This area is of interest to hardly anyone,” says Margot van der Velden, the U.N. World Food Programme’s director of emergencies.

“Until it really, really hits something financial or something political that is actually a direct impact for global players — at this point nobody is truly interested and everyone just stands by watching tragedy develop in front of our eyes.”

Get more info and updates about the Sahel.