Over the years, the names of these countries—among others—have become more and more synonymous with conflict, as civil wars, political instability and changing weather patterns displace people at record rates.

Not too long ago, 80 percent of humanitarian aid went toward countries dealing with natural disasters. Today, 80 percent of humanitarian aid goes toward people in the midst of man-made conflicts. These conflicts are now keeping millions of men, women and children from being able to live in safety, to have access to food, to go to school, to work and earn a livelihood.

Last week, the Stimson Center hosted an event called “Winning the Peace: The Link between Food Insecurity and Global Instability,” named after WFP USA’s recent report. In his introduction, Rick Leach, President and CEO of WFP USA, said, “We all know that war and conflict displace people, disrupt markets, and create food insecurity. But what is shown in this report is that the converse is true as well. Food insecurity also drives conflict.”

Many of the people displaced from their homes—whether still living in-country or crossing borders—do not know where their next meal will come from. For those who attempt to remain in their homes, food insecurity can set off riots and cause a further loss of trust in government.

Panelist Lt. Gen. John G. Castellaw, USMC (Ret.), said that over his more than 35 year career in the Marine Corps, which began just as the Cold War was ending, he saw how the prevention of conflict not only saved lives, but was more cost-effective than helping people rebuild after conflict. Recounting his experience with the military in Djibouti in the early 1990s, he described how they drilled wells closer to communities so water was more easily accessible and vaccinated and dewormed goats which were the main livelihoods for the residents. These interventions helped improve confidence in the government and reduced the opportunity for chaos or the growth of insurgency. He said that while addressing immediate food insecurity is important, these types of long-term approaches are what prevent an escalation of conflict and lead toward peace.

“What we need today in America is to understand that our national power and our security is based on being able to employ all the elements of our national power. Support development, support diplomacy, support those things that engage and contribute to stability and peace and economic stability in other parts of the world,” he said.

Other panelists emphasized this point, adding that humanitarian agencies need a variety of partners to address the increasingly multidimensional reasons for instability in the world.

Dina Esposito, Vice-President of Mercy Corps and former Director of USAID’s Office of Food for Peace, said that private sector engagement has been growing in recent years, bringing valuable knowledge in the fields of technology, logistics and other areas. These partners are helping agencies to deliver aid in complex environments, providing satellite imagery to help monitor migration patterns and pre-position food, and developing new crop varieties that can survive harsh conditions. “There are many positive trends,” she said. “NGOs are increasingly engaged with local actors, meaning there is a greater prospect of sustainability.”

Looking at U.S. investment in humanitarian aid, panelist Chase Sova of WFP USA said that there are three main reasons for continued, and even elevated, support from the government. It is morally right to help those in need and has economically benefited the US by creating new trading partners, but there is also the aspect of national security, where making other countries safer will only help our own. We spend 1.7 trillion dollars annually on military and defense, but only a tenth of that amount on humanitarian and development assistance.

Rick Leach added, “We need to increase understanding as it pertains to political will about why the investments in UN agencies, the investments in NGOs, investments in local capacity building are as important as investments in defense.”

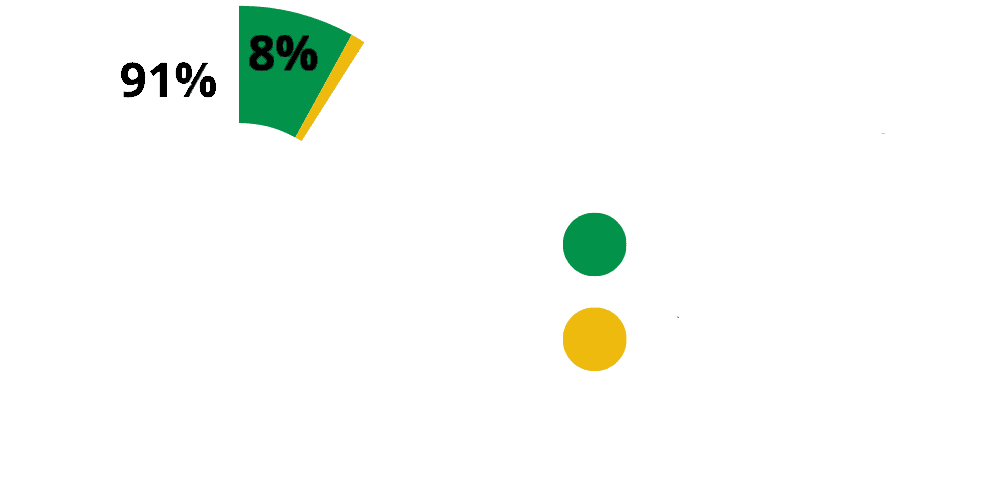

This imbalance is visible globally, as well. In 2017, the U.N. appealed for a record $22.2 billion in aid—a 400 percent increase from ten years ago, largely due to increasing conflict—but was only able to fund just over half of the humanitarian need. The $25.3 billion requested for 2018 has barely received a quarter of its funding as of May.

But history has taught us that we cannot look only year-by-year. We need to take a comprehensive and long-term approach of looking at the root causes of instability and address them. As the foreword of the Stabilization Assistance Review Report by the Department of Defense, State Department and USAID states, “…it is not enough to win the battle. We must also help our local partners secure the peace by using every instrument of our national power.”

“Humanitarian responses are not sprints anymore, they’re long, protracted marathons,” said Dr. Sova. “You have to start getting ahead of these things…making investments that are not purely emergency response, but that help to get countries on the right footing and out of these conflicts.”