George Fominyen still remembers the night war broke out in the world’s youngest nation.

It was a Sunday evening nearly four years ago. George, a communications officer for the World Food Programme (WFP), had gone out to dinner with friends that night in Juba, the capital of South Sudan. On his way home, he noticed an unusually high number of military vehicles on the street. Later that night, the sound of thunder startled him awake.

“I woke up and I thought to myself, That’s curious, why is there rain at this time of the year? It was like rain and thunderstorm. You could hear ‘boom, boom,’” he recalled.

When he looked out the window, there was no rain—only the sound of gunfire cracking and reverberating in the distance. The sound of his phone ringing brought him back inside. It was a message from UN security: Fighting had erupted between the country’s president, vice president and their respective supporters. Humanitarian workers like George were ordered to shelter in place. It was no longer safe to go outside.

He remembers turning on the radio to get more information—and finding the stations eerily silent.

“That was the beginning. In the days that followed, there was a ripple effect. It started in Juba, the capital of South Sudan, then a couple of days later there was fighting in Bor, which was another town in the state called Jonglei, then Bentu.

Then, suddenly, we were in the middle of a civil war.”

On The Brink of Chaos

George first arrived in South Sudan in 2012, less than a year after the country had won independence from Sudan.

WFP/George Fominyen

WFP/George Fominyen

“It was a year of hope,” he said of the atmosphere in what he called “the freshly independent nation.” The country’s fertile Equatoria region, which boasts favorable soil conditions, seemed poised to become a national breadbasket. Finally, South Sudan seemed on the cusp of achieving food security and stability.

“They were barely about to celebrate their first anniversary of independence when I came into the country. Everyone was just looking at what it’s going to be after so many years of struggle to obtain a nation of their own. People were looking ahead.”

George, a former Reuters journalist from Cameroon, said he too had high hopes when he arrived. Now, less than four years later, South Sudan teeters on the brink of starvation.

“It is a cruel tragedy of this war that South Sudan’s breadbasket — a region that a year ago could feed millions — has turned into treacherous killing fields that have forced close to a million to flee in search of safety,” Joanne Mariner, Amnesty International’s senior crisis response adviser, told Bloomberg in July.

The violence has displaced one-third of the country’s population of 12 million, with most families fleeing to makeshift camps, UN compounds or crossing the border into neighboring Uganda, which now hosts one of the world’s largest refugee populations.

WFP/George Fominyen

WFP/George Fominyen

George told me the day he and his colleagues visited the UN base in Juba was the moment he realized how dire the crisis had become—and how quickly. Their visit happened just a few days after fighting first broke out on December 15, 2013. He remembers because many people were traveling. It was almost Christmas.

“That day is the day it dawned on me. I kept saying, ‘If people are hiding here, this many people living in Juba have run into this camp for safety, when are they ever going to get out? And why would they feel so afraid?”

Since then, entire villages have been razed, fields torched and families sent running from their own homes. Meanwhile, agricultural production has fallen and food prices have risen, leaving the poorest households without any means to put meals on the table.

Sounding The Alarm

Earlier this year, the hunger crisis in South Sudan grew so severe that famine was declared in parts of Unity state, where much of the fighting has been concentrated.

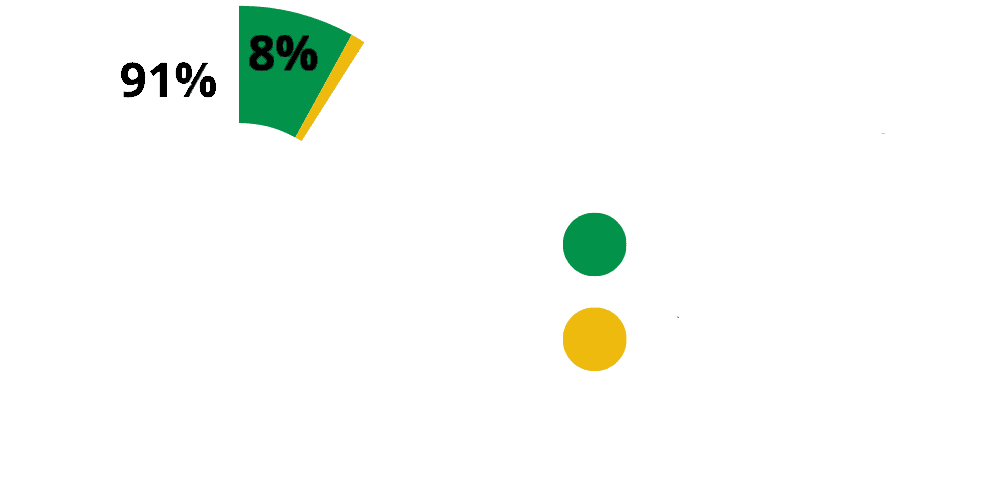

A formal famine declaration means people have already started dying of hunger. Namely, three criteria must be met: 20 percent of the population is experiencing extreme food shortages; the acute malnutrition rate for children exceeds one in three; and one out of every 5,000 people are dying of hunger-related causes every day. Children are almost always a famine’s first victims.

After a colossal humanitarian response in South Sudan, WFP and partners like UNICEF and World Vision successfully managed to reverse the famine conditions in Unity state, but the country remains a Level 3 emergency, the UN’s most serious crisis designation. Right now an estimated 6 million people—roughly half the population—are facing acute levels of hunger, the largest number estimated in the agency’s history.

After a colossal humanitarian response in South Sudan, WFP and partners like UNICEF and World Vision successfully managed to reverse the famine conditions in Unity state, but the country remains a Level 3 emergency, the UN’s most serious crisis designation. Right now an estimated 6 million people—roughly half the population—are facing acute levels of hunger, the largest number estimated in the agency’s history.

Last month WFP reached some 2.7 million people with lifesaving food assistance across South Sudan. But funding shortfalls continue to hamper operations, as does violence that threatens the security of both civilians and the agency’s employees. In April, three of the agency’s contractors were killed on their way to a WFP warehouse.

WFP/George Fominyen

WFP/George Fominyen

Even before the latest conflict broke out in 2013, years of fighting stalled infrastructure development in South Sudan. Less than 200 miles of paved road exist in the entire country.

Meanwhile, an annual rainy season brings torrential rains that flood 60 percent of the country’s few existing roads, turning large swaths of the landscape into impenetrable marshland. Tens of thousands of families have sought refuge in these isolated swamps, relying on water lily bulbs to survive. Reaching people hiding in these remote regions poses serious challenges and risks for humanitarian workers. River canoes can’t transport adequate amounts of food aid. Large trucks often get trapped in the mud. Both are vulnerable to attack.

The fighting—along with non-existent infrastructure and a rainy season that lasts for six months in some places—means WFP must sometimes turn to its last resort for delivering food: Airdrops.

Whatever It Takes

“First thing I want to explain to most people: In South Sudan, airdrops don’t happen in a situation where the plane just flies and drops the food and people rush around and pick it up. That’s a first myth to bust,” George tells me. “It doesn’t happen that way. You need people on the ground.”

WFP/George Fominyen

WFP/George Fominyen

These WFP staff on the ground, known as drop zone coordinators, travel to some of the country’s most dangerous, hard-to-reach locations and work with the community to identify a safe, dry area where as much as 60,000 pounds of food can be safely dropped. Then the coordinator marks the area with a large white “X” in spray paint and clears the space of both people and livestock.

“Because when those bags come down, they could kill someone,” George says of the velocity of these bags, which hold about 110 pounds of food each and plummet from elevations of up to 1,000 feet.

In South Sudan, WFP has joined forces with UNICEF and other humanitarian partners to create Rapid Response Teams that fly in by helicopter to places considered too perilous or remote to reach by road. In a matter of hours, food assessments are conducted to determine who are the most vulnerable families and exactly how much humanitarian aid is needed to help them.

As George explains, the pilots communicate via radio with the drop zone coordinator on the ground, who makes sure there’s no one present— “no animal, nothing, not a cow, not a dog, not a goat around, no one near.” When the drop zone coordinator is absolutely certain the area is cleared, he radios to the pilot: “Cleared to drop.” The plane then swoops in at an elevation of 1,000 feet, opens the hatch and begins to unload the first batch of cargo.

The plane will do several rotations, circling and dropping 10 metric tons with each drop. “So it circles and drops 10 metric tons. It circles and drops another 10, and then circles and drops another 10,” George says. Once the entire cargo is offloaded, the pilot signals to the coordinator on the ground that he’s finished. At this point, work begins to retrieve and count the bags and packages of food scattered across the drop zone.

“We hire local people to be porters and help recover the bags once they’ve landed. Then they’ll stack them, ready,” George says. Registration for each household provides order to the process.

WFP/George Fominyen

WFP/George Fominyen

WFP drop zone coordinator, Kang Koriyom, opens a packet of drinking water after an airdrop in Ganyiel, Unity State.

When weather and ground conditions are good, WFP’s country office in South Sudan can conduct up to 16 airdrops per day, dropping approximately 30 metric tons of food each trip, which can feed some 2,000 people for a month. These food supplies typically include some kind of grain or cereal, such as sorghum or corn, pulses like yellow split peas, beans or lentils, and nutrition products like SuperCereal, which treat and prevent malnutrition among young children, pregnant women and nursing mothers.

Airdrops are considered the last resort because they are generally more expensive and more time-consuming than ground transportation. In recent years, WFP has partnered with U.S. companies to find new ways to deliver food via airdrop. In 2015, for example, the agency engineered the first successful airdrop of fortified vegetable oil using specially engineered parachutes.

Last year alone, these parachute drops saved the agency an estimated $45 million in helicopter fuel in South Sudan. Before this innovation, the agency could only risk dropping bags of grains and pulses that wouldn’t implode upon impact and had to use even more costly helicopter airlifts to deliver fortified vegetable oil and nutrition products to remote communities unreachable by road.

“It really is a sight to behold,” WFP’s South Sudan Country Director Adnan Khan told George earlier this year. “Airdrops of food during the rains when much of the country is cut off from land access are absolutely essential to keep people fed in hard-to-reach areas.”

These airdrops have become such a common sight in South Sudan’s Unity State that children there have started making toy versions out of mud. Seven-year-old Peter Mabor, pictured below, told George he likes to play with his toy plane as he watches WFP’s food drop from the sky. In South Sudan, the agency’s planes are called “gwads,” or large wings.

In a 60 Minutes segment in March about the crisis in South Sudan, CBS correspondent Scott Pelley described WFP’s airdrop operations as “manna from heaven.”

WFP/George Fominyen

WFP/George Fominyen

Seven-year-old Peter Mabor likes to watch WFP’s planes fly overhead and offload cargo in Unity State, South Sudan. Peter tells George he’s observed it so many times that he knows how to construct toy versions of the plane using mud.

After spending almost five years in Juba as a communications officer with WFP, George was reassigned this year to a new post. When I asked him how he felt about leaving South Sudan, his eyes betrayed his sadness.

“I’m from Cameroon,” he told me. “But after being there for so long, I feel South Sudanese.

There’s a lot of South Sudan in my heart.

As I wrote to colleagues on the day I left the country: The people’s stories of joy, pain, suffering and hope will always remain with me. All I wish for South Sudan is peace and prosperity.”