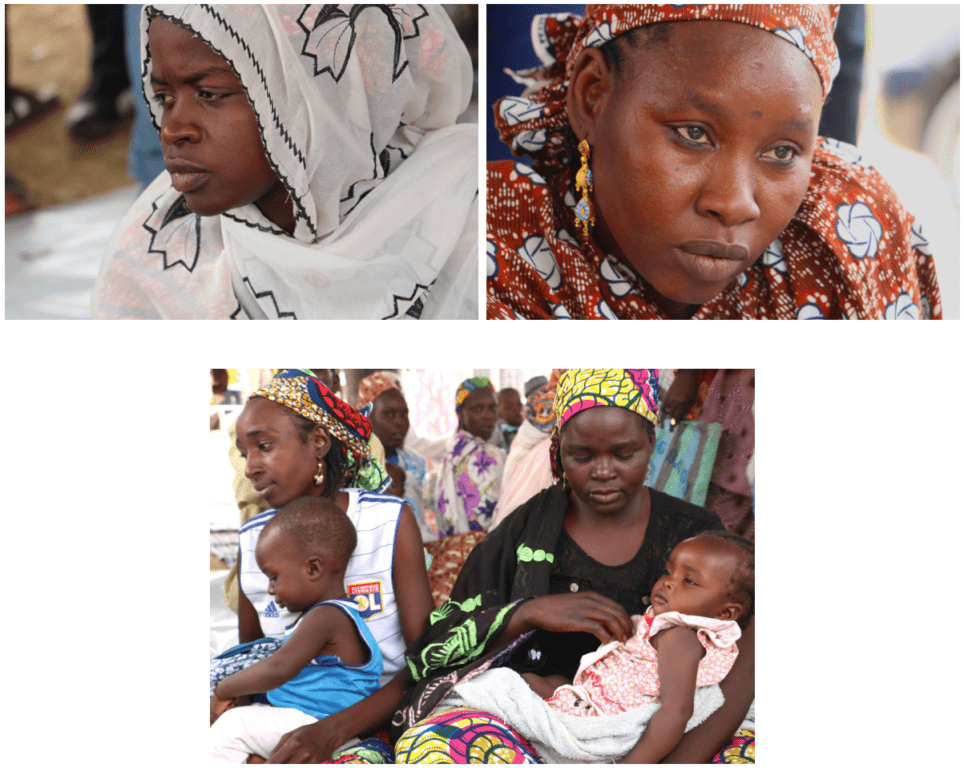

The Women and Girls Uprooted by Boko Haram

In northern Nigeria, the number of school children has dropped from nearly 500,000 to about 130,000.

Nine in ten people uprooted by Boko Haram — about 2.2 million people — live with local communities, not at formal sites. Both those displaced and the local communities hosting them suffer from hunger.

To survive, many have to resort to begging, taking their children out of school and engaging in poorly paid labor. They live hand to mouth.

Maiduguri, Nigeria

They once had homes, close-knit communities, herds of animals and fields of crops. They are now taking refuge in a dilapidated school building. Their stories are heartbreaking.

“When we arrived, we found all the windows broken,” says one young mother. “There is no running water. We have been living like this for two years. It has been difficult…I didn’t eat today…But, at least, here we are a community. We have all fled the same village.”

“I lost my husband to Boko Haram. There are many other women like me here,” says Amina, a mom of four (below).

“I like math. I like to go to school,” says Haira (below). She has been living in the former school building with a part of her family. She considers herself lucky. Most children of the nearly 100 families taking refuge in the former school can’t afford an education for their children.

Lake Chad Region, Chad

They used to grow their own food, look after their animals, and their husbands fished for a living. About 80,000 people were uprooted following attacks and threats from Boko Haram, and now live in harsh conditions, in desolate fields of sand dunes.

“We used to eat fish and cassava. We had our farms and could grow our food,” says Isara (below), now living in relative safety at the Yokoua displaced people’s site. She’s been here since June, when her island village was attacked by Boko Haram.

“We couldn’t even bring our clothes. The families living here helped us out when we arrived, and we got some food from WFP. But we’re still suffering.”

As the lean season is fast approaching, children and pregnant and nursing women are at risk of growing malnutrition. At 13 percent, the prevalence of malnutrition in the Lake Chad region of Chad has already exceeded World Health Organization emergency levels — a marked deterioration since 2012.

Mokolo, Far North Region, Cameroon

In the areas worst affected by the Boko Haram violence, over one-third of the population faces hunger. Over 70% of the farmers have abandoned their fields due to ongoing insecurity.

“ I came here with my nine children. My husband got killed. We don’t have anything to return to. Our house got burned down…I try to sell peanut oil to survive,” says Haram (below).

“I want to be a soldier. To bring peace. To fight those who caused this,” says 10-year-old Aisha. Her dream is a stark reflection of what she has survived.

“What do we need?,” asks another mother. “We need food, money to pay for where we live. We have no mattresses or clothes for the children…With a little support, we would be able to get on our feet. To send our children to school. To earn a living.”

In response to rising food insecurity, malnutrition concerns and continued displacement in the Lake Chad Basin, the UN World Food Programme (WFP) aims to scale up its assistance.

WFP needs urgent support to continue to provide food and nutritional assistance to displaced and vulnerable host communities alike. To date, only 17 percent of the required funding has been secured.

This story was originally written and photographed by Adel Sarkozi on WFP’s Insights.